He's out here hitting, getting hit ... living the dream.

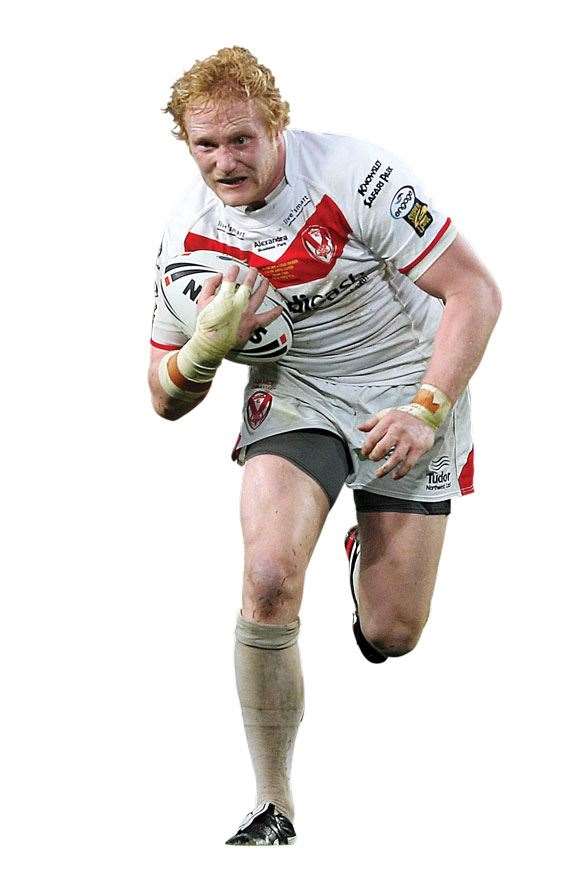

JAMES GRAHAM IS A HARD-KNUCKLED boulder of a man, a golden-haired warrior with a glowing moon tan, a woolly red beard and a blond-rust nut. It’s hard to think of anyone he looks like; it’s a singularly interesting look. But it sort of suits him, the golden warrior thing, just as it might an Irish Viking.

Inside Sport is sideline at ANZ Stadium for the Canterbury-Bankstown Bulldogs’ Round 14 game against the Parramatta Eels. And we’re focusing on our man Graham, alone, all game, because it’s an instructive thing to do. You see stuff.

The ’Dogs trot out to warm-up and, if you look close enough, you note the very slightest of struts in Graham’s carriage. It’s not arrogant. It’s just the certain co-ordinated human movement of your top-level sporto. He’s not sticking his arse out like Viv Richards and hasn’t got himself a pair of bubble-gum-coloured footy boots like the fancier pants men. Indeed, he wears the black boots of the tradesman. But when Graham is that side of the stripe he’s a big dog, a barrel-chested Buzz Lightyear. Graham knows he can play. He’s always known.

Kick-off and our Viking tears arse upfield, makes the first tackle, front-on, chest-to-chest. It’s not a “hit” per se, he more sort of leans in and uses his bulk as ballast. And a big Eel makes no further forward progress.

The ’Dogs head into this fixture without their Origin halves and talented colt Moses Mbye – which means they have two hookers, a back-rower at five-eighth, I think, and later centre, and Tony “T-Rex” Williams feeds scrums. It’s a hot-potch of humanity. And Graham, a prop, is often first off the ruck.

When zippy Eel Chris Sandow splits the ’Dogs to run 80 metres, this way and that, Graham is, somehow, tackling a winger around the ankles to stymy the movement in the corner. No right to be there. It’s clear the man has some engine. Indeed he’ll play 75-straight minutes today, a lot for a modern-day big lump, coming off only when the game is toast. And there he sits, riding his bench seat, blowing hard, engaging in post-mortem conversation with whoever will listen. Man is breathing this game.

And why wouldn’t Des Hasler keep his orange roughie on the paddock as long as he can? For Graham is a bunch of players. Middle of the park he’s a talker, an organiser, a distributor, a rumbler – whatever’s required. He’s a busy footballer, carting it up or slinging it wide. He throws short balls and long ones. He offloads. His passes that angle backwards almost 45 degrees, those babies can set speed-freaks free.

Now in his third season of this National Rugby League after nine years a pro at St Helens, the 2008 “Man of Steel” (awarded to the best man in Super League) is 28-years-old and prime. And he is, perhaps, arguably, the most influential English prop-forward we’ve ever seen.

SCOUSER

Liverpool to St Helens is 20 kilometres as the crow files, or a half-hour drive on the M62. Yet in the way of the UK, people from these places have different accents, funny names for each other and tastes in sport. Liverpudlians like football of two types – red or blue. St Helens folk like “roogby” that we’d call rugby league.

Graham was born in Maghull, Merseyside, which makes him a “Scouser”, according to mates. They reckon his accent’s been Australian-ised, a bit, but I can’t hear it. To this Aussie he’s equal parts Ringo and George. Graham came to rugby league because his old man, John, was a league fan. Didn’t have a team, John, just liked the game. Every year John and his old man, James’ grandad, would head to the Challenge Cup Final at Wembley. In 1993 it was Wigan and Widnes. Before boarding the bus, John picked up some refreshments for the trip down and saw an advertisement in a shop-front window: “St Helens Crusaders U/8s Seek Players”.

“We’ll see if our James fancies that,” John told his dad. A couple of days later he asked the boy: “What do you think about playing rugby?” The young fellow was nonplussed at first. He’d never even heard of it. Sport for a Scouse kid was soccer in a park, jumpers for posts. But he told the old man he’d give it a try.

John bought him boots and a ball, and took him to the park, put up some bombs. Wednesday night they headed to training, where there was actually a game. James didn’t know the rules – thought it might be like American football. But the coach pitched him in. And the boy loved it. “I was like, ‘How’s good’s this?’” says Graham. “It seemed like a crazy sport. They asked, ‘Do you wanna come back?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ Saturday we had training, played the Sunday. And I was instantly in love with it.”

A chunky lump of a kid, Graham loved the game’s physicality. He wasn’t much built for the round-ball sport. And he found league tremendous fun. He made a few rep teams. Even played on Wembley aged 11. By the time he was 16 he’d signed with St Helens. And according to a team-mate at Blackbrook Junior and Amateur Rugby League Club, Greg Peters, what you see now is what opponents saw then. “He was always bigger, much bigger than other kids,” says Peters. “Faster, stronger. Parents were always saying, ‘Don’t worry, next year you’ll all be the same size, and catch him up.’ But we never did. If anything, he got bigger again! Nobody ever caught him.”

Peters says Graham “could always do a little bit with the ball. He wasn’t just big. You didn’t know if he was going to run the ball, pass the ball, sidestep, run straight – he was always asking questions. He played against us before joining us, and we had some brave lads. But our best players, you didn’t know what he was going to do.

“And he’s never changed. What you see now is what he’s always been but on a smaller scale. Always did the full 80 minutes, always wore his heart on his sleeve. I remember a game that was particularly wet and horrible. First minute, the ball was loose on our tryline in a pile of sludge and mud. A couple of our lads were hanging off. Out of nowhere James came flying in, skidded over, sent mud and water flying everywhere and grabbed the ball. He was covered in mud and crap the whole game. Wasn’t bothered.”

Competitive, then? “Very. Remember when he first got to Australia [in 2012] he put some Vaseline on his legs? Got warned off it, or something? Well, he did the same as a kid. He used to carry around a little bottle of cooking oil, rub it all over him so we couldn’t tackle him. He was too slippery.”

Yet not all of Graham’s opponents could be so easily beaten.

“We were on a night out, between pubs, looking for taxis,” says Peters. “And we lost him. And we looked around – where is he? And he was down the road, 50 yards away, and he’s trying to knock a wall down by running into it. We were like, ‘James, what are you doing?’ He was like, ‘I’m going to knock this wall down!’ He was doing his best.”

What sort've wall was it? Cobblestone? Brick? “It were the side of a building! He was taking a ten-yard run up, giving it everything. It might be where he got his technique from. People used to say of James that he’d run at a brick wall. Well, he actually did.

“We were about 18,” adds Peters. “We hadn’t been drinking very long.”

Graham says from about age 15 he was dedicated to playing professional rugby league. There were two seminal moments on his journey. One was a trip to Cardiff, aged 18, and standing in the middle of mighty Millennium Stadium, a non-playing reserve for the 2002 Challenge Cup final against Wigan. “I remember being middle of the pitch, thinking, ‘Wow. I want to be a part of this. Next time St Helens win a trophy, I want to be on that field.’ It was a goal and I was lucky enough to achieve it.”

Three years earlier Graham came to Australia for the first time, on tour. It was great, almost exotic, for a young Englishman to play against counterparts in Australia and New Zealand. Aged 18, he toured again.

“It was bizarre,” says Graham. “You grow up your whole life playing English kids. And Australian and New Zealand rugby is held in such high regard. And you don’t know how good these kids are going to be. It was a strange feeling to test ourselves against the best 15-year-olds, the best 18-year olds in Australia, New Zealand. It did a lot for me personally. It was the first time you’re in that full-time environment. Until then, you’d go to school, train. Play on weekends. But on tour it was like, wake up, breakfast, train, lunch, train. It was new and I was like, this is what it’s like to be a full-time rugby league player. For a job. And it was something that drove me. I like doing this.

“And from those tours I dared to dream about a career in Australia. And if the opportunity ever came up, I’d have to think about it. And luckily the opportunity came.”

BELMORE

We’re at Belmore Oval, the maggoty old rugby league ground with a train line running the northern end, a big swadge of grass to the east and the blood of old Berries in the sticky black dirt. It’s here that one-time Bulldogs CEO Todd Greenberg convinced Graham that this should be his rugby league home. It must’ve been some sell. For when Poms think of Australia, it’s generally Bondi Beach and old mate and his “flaming galahs” – not low-rent red-brick ’burbs, rusty signs on ancient butchers and Terry Lamb Reserve.

Yet within the bowels of this venerable stadium is all the high-performance kit-and-kaboodle a pro footy man needs. Physios and ice baths, all that stuff. And pro footballer, ultimately, is what J. Graham is – and he’s still pinching himself about it.

We meet the man in a blue seat on the sideline at Belmore on a chilly winter day. He’s wearing a sloppy joe and footy shorts, but doesn’t appear to be cold. There’s a ready smile and handshake, and despite warnings he might keep things to himself, there doesn’t seem any wariness or antipathy for a member of a profession that’s given him some gip in recent years. (We’ll see how he goes with the last couple of questions.)

And so we turn on the tape, and wonder, How did Greenberg and the Dog People convince him to come here? Why here? “I’d had a desire to come out for a while,” says Graham. “I’d been at Saints; there were five or six of us who came through together; we were a really close-knit bunch. Some great Australian guys, who I still keep in touch with. Great bunch of lads, so much fun. And we really trained and played hard.

“But I guess I realised I’d done nine years there as a professional and it was pretty much now or never. If I’d signed a long-term deal at Saints, the ship would’ve sailed. And I wanted to come to Australia.

“So I got involved with [player agent] Dave Riolo to act on my behalf, kind of thing. And I came over here for the 2010 Four Nations. I got permission off Saints to speak with Canterbury, who’d shown interest, and Todd Greenberg, Kevin Moore. And they really sold me on the direction of the club. They were keen to have me. Todd played a massive part. I didn’t need much selling, but they explained what was going on.”

Graham’s first NRL game was at Penrith, nudging 30 degrees. “I remember it well; I dropped the ball first touch off a tap,” he smiles. “Very nervous that day. I’d played a couple of trials. Not the same. And to go to Penrith, after a long, hard pre-season to wear the shirt for the first time was something I’d thought about a lot. I’d been signed for a year until I made the debut. And there was a lot of self-doubt. The NRL, you watch it on TV, it’s hyped up a lot in England. I doubted whether I could perform or be out of my depth.”

Really? But you had already played for England. Nine years with St Helen’s ...

“I genuinely didn’t know,” says Graham. “There was a lot of self-doubt. But I thought I did okay. I was like, ‘I can tackle them, I can run into them without getting belted.’”

And so into a season with the ’Dogs in which Ben Barba scorched the earth and Des Hasler unleashed a pack of big Dogs who would, incredibly in a game as risk-averse as pro league can be, pass the ball to one another. Graham says it was tremendous fun.

“It was a really great year. It’s important that you make rugby fun. There’s a time to be serious but you’ve got to make it fun. Corey Payne was here and he was in his element. Fun guy to be around. We did fall short at the final hurdle. But we won a minor premiership. And there were times as forwards that they’d put us under pressure with a kick and you’d look back, oh god, I’m tired, and next minute Benny Barba’s run 90 metres and put it down middle of the sticks. It’s always nice to be on the field with someone who can do that.”

And then you ask the man, because you must – it’s what you do – about the “Billy Slater incident” in the 2012 grand final. The one that saw Graham suspended for 12 weeks for appearing to chow down on Slater’s ear in a wild melee near the corner flag. And you’re halfway through asking and it might be your imagination (but it’s not), but the Irish Viking’s stare gets just that tad more ... focused. Intense. His brow furrows just slightly and settles there, still, above his eyes, a bit like The Thing’s. He knew this was coming. Doesn’t mean he has to like it.

So – do you think you were fairly treated by the judiciary regarding the biting charge? You went into it saying you didn’t do it. Do you still maintain that? Where are you at with all that?

He looks away. Looks back at you. And says: “Yeah, to be honest, I’ve just moved on. I’ve just completely and utterly moved on from it. At the time ... it was ... Yeah, I just ... I went home. I had feelings on some things. But I’ve left that behind me now.

“People, like yourself, maybe want to talk about it. But to be honest, I can’t be bothered re-opening it again.

“You know what, we’ve been talking about me growing up with the game, and loving it. I’ll tell you this: I’d have been happy to play one game of professional rugby league. I’d have done anything for one game. Absolutely anything. That this is my job ... sometimes I still can’t believe it.

“And in trying to take positives from things [being suspended] gave me that love for the game back. No, not ‘back’. But it made me appreciate the game more. The game had been taken away and I couldn’t do something that I loved doing. I hate myself for doing it, but you can forget how good the game is and coming to training is. It took away any complacency.

“But as far as anything to do with that incident, I’ve totally moved on.”

And where is he now with the media? There was something of a storm at the time, which can’t be pleasant. Lot of cameras. Some fool lobbed at the judiciary in a Hannibal Lecter mask. Was Graham dark on the press for its reportage?

“To be honest, I didn’t read any of the papers, so I wouldn’t know.”

What about being hounded by cameras? There was a heap at Belmore at your grand final muck-around ...

“Obviously we were here for Mad Monday, and yeah, I had heard that there were cameras and stuff here but ... I mean, that’s their prerogative. Sometimes I think that the media can’t wait for people to fail. I have the attitude that all they’re trying to do is nail a coach, nail a team, nail a player. They just sometimes can’t wait for someone to muck up. But then that’s their business. And if someone isn’t performing or a coach is under pressure, writing about that sells papers. Negative stories, people want to read them. That’s what society wants to read about, so they’ll report it.”

THE END

Graham is signed to Belmore until 2018, after which he’ll have the agreeable problem of deciding what to do with his life. He’ll take it as it comes, but admits to a niggling desire to play a season or two more with St Helens. After that he’d like to coach. Quite a lot, as it turns out. “I’m halfway through a coaching course, so I’d like to get that finished. There’s a big desire to get into coaching, big passion. But then looking at the gaffers’ stress levels, maybe not! In all seriousness, it’s a huge ambition to get into coaching and succeed at it. But it’s a few years away yet.

“And being a Saints supporter since I was eight, there’s a part of me that’d like to finish my career with Saints. The club’s been my life for 20 years and it still is. I’m always looking at results and watching games. It’s actually nice to be a fan.

“But whether I go back or stay, it’ll be circumstantial, and I’ll decide at the time.”

Away from footy, Graham is not a surfer (“human beings evolved from the water and I see no need to go back there”), golfer or Xbox jockey. Indeed he admits he “doesn’t really do anything”.

“It’s a bit sad, actually,” he smiles. “I really don’t. When the time is right, I go down the pub and have a few beers. During the week go out for coffees and watch the world go by. Pretty simple, really.” Half his luck. Good fellah. Good luck to him.

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open