The targets of rugby league legend John Peard’s “bombs” were his fellow attackers, and very nervous defences.

The targets of rugby league legend John Peard’s “bombs” were his fellow attackers, and very nervous defences.

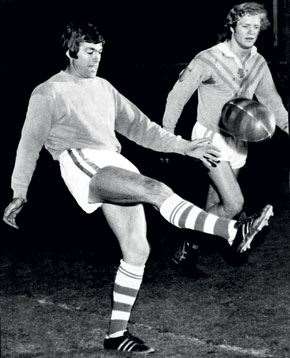

John “The Bomber” Peard was the most feared man in rugby league. Image: Newspix

John “The Bomber” Peard was the most feared man in rugby league. Image: NewspixLong before John Peard became “The Bomber”, when he was playing for Eastern Suburbs in 1966, the game ground away under the old unlimited tackle rule. Under that gruelling regime, St George had won 11 premierships in a row. Rugby league was about possession. The Dragons ceded possession when they felt like softening the opposition up with their punishing forward pack, and regained and kept it the rest of the time.

The introduction of the four-tackle rule in 1967 (later extended to six tackles in 1971) changed all that. As the tackle count wound down and the pressure mounted on an attacking team to create scoring opportunities, it was only natural that field kicking in general play would become more of a feature.

By that time, Peard had already proved a talented five-eighth for Easts and Saints. In 1974 he returned to the Roosters. Under the inspired Jack Gibson and supported by fast and bullocking backs like Ian Schubert, Bill Mullins, Mark Harris and the mercurial Johnny “Monkey” Mayes and Russell Fairfax, Peard instituted the use of the “bomb”, or, as English commentator Eddie Waring dubbed it, the “up-and-under” kick.

Peard may not have invented the concept of the up-and-under as a legitimate attacking weapon, but he was its first exponent. Peard’s towering “bomb”, as it quickly came to be known, deserved the epithet. Holding the ball perpendicularly with a hand on either side and booting its bottom point, Peard would send it spiralling vertically skyward, end-on-end. The ball would travel high, but not far, and once it was up there, it was subject to the elements. Once at its zenith, it would drop out of the sky like Fat Boy. The effect on the opposition defence – on rugby league itself – was profound.

Peard’s execution was far in advance of anyone else’s in the game. He used the bomb relatively sparingly but to great effect in 1974, the year Easts first dominated the competition and won the premiership. In 1975, when they repeated the triumph, it was used a little more. The sight of the little five-eighth shaping up for the kick, especially late in the tackle count, inside their 25, caused tremors in the opposition defence. Used to moving up and grinding out the sixth tackle, they were now in two minds.

Suddenly, Peard was testing the mettle of some of the best fullbacks the game had seen, like Graeme Langlands and Graham Eadie. Rugby league was unaccustomed to the sight of men like Jim Porter and, later, Ray Price leaping above a pack, Aussie rules style, catching the ball and scoring tries. Today, it’s not only commonplace, but a spectacular feature of the game.Peard, the ingenious mischief in the Eastern Suburbs machine, helped them to win 39 of 44 games in those two seasons. In 1976 he moved to Parramatta, and a new era began for the Eels. Coach Terry Fearnley was keen to further exploit Peard’s revolutionary skill.

Now a fixture in the Australian Kangaroos and New South Wales Blues sides, Peard took control of an Eels team featuring Ray Higgs, Geoff Gerard, Price, Mick Cronin, Ron Hilditch and Denis Fitzgerald. They accounted for St George and Manly to reach

their first ever grand final, a close match which they lost to the powerful Sea Eagles. They repeated the effort the next year. The gruelling drawn 1977 grand final against St George almost changed completely in Parramatta’s favour when Fearnley brought the injured Bomber on in the second half.

By the 1980s, the bomb came to be seen as a blight on the game; a “negative” tactic, and was legislated against. A kick caught on the full in the in-goal area by the defending side now resulted in an automatic 20m tap restart.But John Peard had forever altered the role of kicking. After his retirement in1978, players such as Peter Sterling, Steve Mortimer, Allan Langer, Ricky Stuart, Brad Fittler and Andrew Johns mastered versions of attacking kicks. It opened the way for the use of the winger-targeting cross-field bomb.

The game’s modern incarnation can be traced directly back to the day little Johnny Peard transformed himself from a very good link man into The Bomber, the most feared man in rugby league.

– Robert Drane

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open