Never before or since has a player boasting the toughness and smarts of “Lethal” been seen on an Aussie rules field.

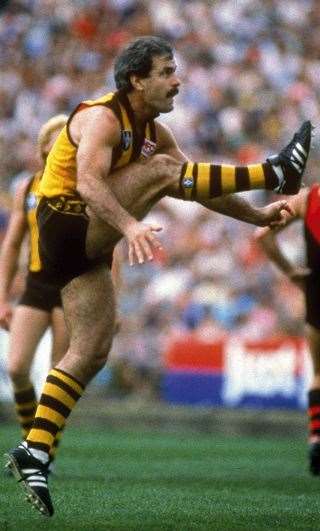

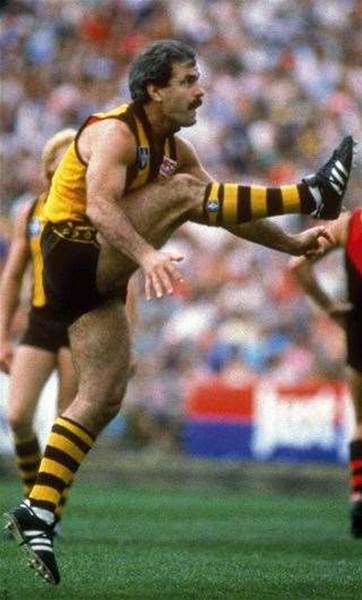

Built low to the ground, “Lethal” boasted enormous power through his hips and thighs. Photo: Getty Images

Built low to the ground, “Lethal” boasted enormous power through his hips and thighs. Photo: Getty ImagesThere’s no one innovation Leigh Matthews can be credited with. He’s one of God’s innovations and, as such, the author of many firsts. Matthews was unique: rarely has a player so tough, ruthless and physically damaging also been one of the smartest ever to play. His ability to give and take punishment, combined with extraordinary ball-getting prowess and an instinct for the flow of a game that bordered on supernatural, led him to be adjudged the Player of the 20th Century.

Though such awards can’t be anything but subjective, it was a fitting accolade for a player who was not only sui generis, but the match-winner supreme. When it comes to games of footy influenced by one man’s play, and sometimes by his mere presence, no player – not even Wayne Carey – comes close. Matthews played in some of the most talented Hawthorn teams – the most talented of any colour – yet he won the club’s Best and Fairest eight times.

Matthews’ influence on a game was sometimes just enough to get his teams of champions over the line when magic was required. Oft-times that influence was simply devastating, measured not only in goals and behinds, but body counts and psychological money in the bank against top sides like Barassi’s North Melbourne, a team he destroyed on many occasions.

Lethal Leigh was short for an AFL player, but at 178cm, wasn’t as short as many thought he was. Matthews was heavy and hard-boned, yet a quick mover. Low to the ground, with enormous power through the hips and a high-tensile core strength, he was almost impossible to grab. He had a way of violently twisting, wriggling and banging his way out of intended tackles on his single-minded quest to goal. Few footballers were ever more complete.

Unlike his fellow rover and contemporary, Kevin Bartlett, who ran all day and was almost impossible to touch, Matthews either ran over opponents or outsmarted them. His ability to time a cruel hit made him the most feared man in the competition. Opponents spent entire games as far away from him as they could get. Indeed, Matthews ended many a man’s match, and the odd career, with one fierce knock off the ball. Many of today’s tough “in-and-under” midfielders should count themselves lucky they never played against Matthews. It might have been in, under and out ...

His cunning on the field and ability to deliver was something his team-mates, many of them highly-esteemed greats of footy, thrived on as he set them up with voluminous disposals, or simply kept the score ticking over by himself. His 915 goals was a VFL career record for majors by a non-full-forward. Matthews played some truly amazing seasons of football.

While still a teenager, he quickly developed a reputation for an uncanny ability to get the ball and use it with maximum results, and for brutal physicality. (A little-known fact nowadays is that he was already gaining a reputation as a media commentator as well during that period with his astute analyses in The Sporting Globe.) He performed his role of crumbing to record-breaking full-forward Peter Hudson to great effect, and once, when Hudson was absent, the 19-year-old kicked eight goals. He became renowned for breaking loose with big tallies. In 1973 he kicked 11 in a game against Essendon.

The next year he destroyed Collingwood in a semi-final with seven. In 1975 he won the Coleman Medal (the VFL/AFL goalkicking award), and got 91 in 1977 – a year in which he dominated the competition. The season tally was also a record for a non-full-forward. He averaged over 27 disposals per game that year.

Enhancing Matthews’ legend is his still-talked-about toughness; in addition to his prodigious tallies are memories like the time he snapped a point post in half when he ran into it at Windy Hill in 1982.

Matthews took his penetrating logic, physical approach and – at times – insightful psychology into coaching. First at Collingwood, who he steered to their first premiership in 32 years in 1990, and then, after a three-year break, at the Brisbane Lions, where he snapped up another three premierships between 2001-03.

The first of those titles was no “gimme”, as the 2000 Essendon premiership side was considered unbeatable – one of the best ever. But before their round-ten game, Lethal Leigh typically gave everyone second thoughts and galvanised his team with one frank public observation. When asked about his team’s chances,

he produced a quote from the movie Predator: “If it bleeds, we can kill it.” The Lions scored an unlikely win. It transformed them overnight.

Like the creature in that movie, Matthews, as coach and player, was tough, smart, destructive and you never knew where he would turn up and what damage he’d do when he got there. Matthews’ coaching record is up there with the best. Little wonder that much-deserved nickname, “Lethal”, never left him.

− Robert Drane

Related Articles

Will our Olympians bounce back at this year's Games?

Ella Nelson has already beaten a few of world's best

.png&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)