The founder of a sports journalism institution was in it for much more than magazine sales. Put simply, Australian boxing needed Fighter.

Mike Ryan is the pioneering founder-editor of Australia’s first successful and most long-lived boxing magazine, Fighter. Ryan started the mag with a dream of bringing emerging stars like Lionel Rose, Johnny Famechon and Bobby Dunlop into the mainstream.

Mike Ryan is the pioneering founder-editor of Australia’s first successful and most long-lived boxing magazine, Fighter. Ryan started the mag with a dream of bringing emerging stars like Lionel Rose, Johnny Famechon and Bobby Dunlop into the mainstream.

It wasn’t easy for a lone man to establish a magazine; Ryan started one that lasted 35 years. During that time it flickered, it faltered, but for a time, it shone brightly.

Ryan began Fighter after returning from England, convincing his overlords at The Age, where he worked as a senior journalist, to ride boxing’s new wave of popularity and get into magazines. With The Age managing director Ranald MacDonald, Ryan became co-partner in the venture. The first three covers, October, November and December 1967, featured portraits of those three champions.

Lack of profitability led MacDonald to relinquish Fighter. Ryan bought his share for one dollar and started a company with Kiwi real estate mogul Robert Jones. That also went bust, and Ryan, an energetic and determined character who always thinks big, made the decision to keep the title going while still working at The Age. In his “spare” time he produced an innovative magazine that won the sport new fans.

Mike eventually became full-time editor and moved into a Toorak office. The inquisitive Ryan was, and still is, a can-do man. It was no small task. Nat Fleischer established Ring magazine in the States, and was editor for 50 years. But America is the land of opportunity. If you wanted to start a magazine, you’d have a readership; a boutique rag on an esoteric subject would enjoy greater circulation than an Australian mainstream publication.

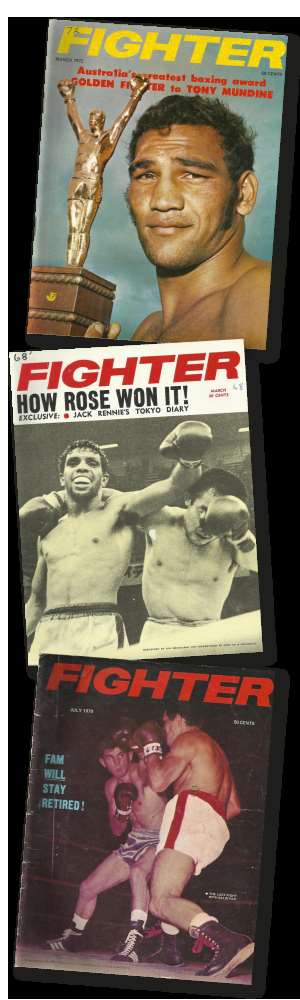

It’s rare in Australia that the little man gets a look-in. Ryan’s approach was simple. The glossy cover always featured a colourful, themed portrait or action shot. It was never overburdened with cover- lines. One was often enough. That first issue featured a smiling Lionel Rose, pre-world championship, and the solitary coverline proclaimed “Rose takes on the world”. Fighter always shouted loudly from crowded newsstands.

But Ryan was never content to be a mere passive recorder. Through Fighter, he wanted to improve the sport and the lot of its practitioners. He understood the benefit of symbolically establishing a magazine in the public mind by conferring awards, and had a statue fashioned by the sculptor Ernesto Murgo, The Golden Fighter – a yearly award which Fighter presented on television to the boxer Ryan’s stable of writers deemed fighter of the year. With his eye for the main chance, Ryan ensured that Fighter’s version of the Fight of the Century (Ali-Frazier in March 1971), written by his New York correspondent Eddie Cool, hit the stands in the USA before any of their own magazines managed it. It sold out instantly.

He also employed a female co-editor, Bev Will.

Internationally, boxing magazines never featured a female voice. America’s Ring magazine ran a story on Will in 1972. Bev wrote elegant prose, and described fights and fighters in ways male reporters never considered. Of course, she was unfairly criticised.

Will and Ryan campaigned for better conditions for boxers. Fighter became an influence in the sport it reported – a rare phenomenon in Australia. During Fighter’s first years of publication, three men died in the ring. Two others were permanently disabled. The intrepid Ryan and Will discovered several of these boxers had pre-existing conditions that would have been detected by electroencephalograph and for the next few years they lobbied tirelessly, approaching the medical profession to ensure that anyone entering a ring be subjected to compulsory EEG testing. They published their findings in Fighter. But the medical profession never really came to the party, and today, despite those early attempts at rapprochement, it rails against boxing.

Ryan and Will would often have “Rose” and “Fammo” around to the office to discuss the future of Australian boxing over sandwiches, and occasionally they’d feature these round-table discussions in Fighter. The two of them wrote most of the features until they established an impressive stable of writers and photographers here and overseas.

Every year, Ryan, a literary ex-pug, would bring out an annual, Fighterbook, showcasing some great writing on the fight game. As a kid, I was a fight fan, but had no idea people could write about boxing the way the quirky Ryan and Will did. Then, in Fighterbook, I read Norman Mailer’s account of the death of Benny Paret at the hands of Emile Griffith, and discovered that boxing writing could be high literature.

As the 1980s ground on, boxing waned. Television, its Mephistophelian friend, both made the fight game and broke it. Boxing had too many sanctioning bodies and “world champions” were beginning to proliferate. Fighter’s circulation slumped, but it fought well into the 2000s.

In his 70s, Ryan stayed devoted to boxing, even trying an online edition of Fighter. Today, at 80, he never tires in his quest to find new ways to report, and improve, the fight game.

− Robert Drane

Related Articles

Heavy hitter: coach reveals life post Clubbies

UFC243: Will this end Aussie's five year undefeated run?