Unlike their US colleagues, it’s never been Australian sportstars’ way to stop playing during pay disputes ... but for how much longer?

Unlike their US colleagues, it’s never been Australian sportstars’ way to stop playing during pay disputes ... but for how much longer?

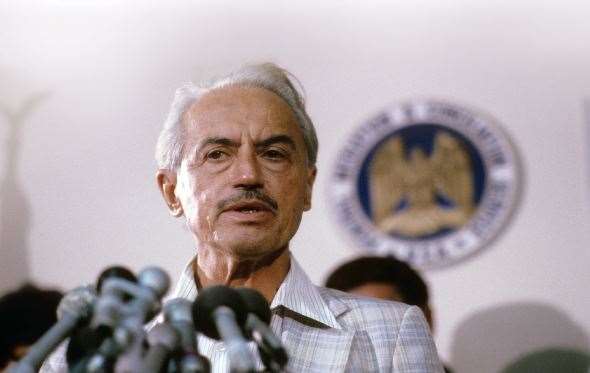

Marvin Miller took on a system in which players had next-to-no bargaining power. Image: Getty Images

Marvin Miller took on a system in which players had next-to-no bargaining power. Image: Getty ImagesThere’s a phenomenon in player industrial action, unscientifically observed by your columnist. Whenever the leaders of the players’ association or union happen to be the sport’s big stars (rather than some respected, yet lower-profile veteran), count on the action being more serious. The logic here: when top players are motivated enough to care about the rest of their colleagues, rather than just counting their own money, that’s usually a good sign for player solidarity.

That’s why it was interesting to see who was in the rugby league players’ delegation in its meetings late last year with the NRL about salary cap increases. Gallen, Farah, Thurston, Smith, Hayne, among others involved – a statement of intent from the league boys, who seem to understand that at this moment the stakes are high. Against the trend in every other form of entertainment, the money in sport continues to grow, as do the struggles over how to distribute it. And it’s happening everywhere; the most extreme example is ice hockey in North America, where only eight years after losing an entire season, the NHL has stopped playing again.

We’ve grown used to the sight of big-name athletes asserting their worth, but it was the recent passing of a lesser-known, rather unassuming figure that underlined how sports have arrived at this place. Even to people who follow baseball, Marvin Miller is not an instantly recognisable name. It’s curious, because Miller looms large over the American pastime as well as an increasingly large chunk of sports history in general.

In the niche field of labour relations in sports, Miller is a titan. He was an economist for the steelworkers’ union when he took over the rather ineffectual baseball players’ association in the mid-1960s. Miller’s first great impact, according to University of Melbourne legal scholar and baseball enthusiast Braham Dabscheck, was to convince the players that their association “was not a social club”.

Over the next decade and a half, Miller and the union took on a system in which players had next-to-no bargaining power. The key feature was known as the reserve clause, under which a player’s rights were retained by his team even at the end of his contract – in effect, every player was signed to a series of one-year deals, with no leverage to switch teams or negotiate for a better deal.

“He stood up to the owners and said, ‘You guys can’t do this,’” Dabscheck says. “The players saw in him – the players are very competitive by nature, you only have to meet them to know that – someone who was as competitive in the boardroom as they were on the diamond.”

The concessions that Miller and the union won are now part of the professional sports landscape: the first collective bargaining agreement, pension plans, increases in the minimum and average salary, the end of the reserve clause and genuine free agency. To get there, the major leagues endured five work stoppages, with player strikes in 1972 and ’81 causing the cancellation of games. As one team official bitterly put it, Tojo and Hirohito couldn’t force baseball to stop, but Miller could.

The rancour that baseball’s powers-that-be held for Miller ran extremely deep. They dreaded negotiating with his infuriating mix of mild-mannered implacability (it was said the only laughter you’d hear from him was a low-key chuckle at unfunny moments). Having taken a position, Miller was impossible to budge; even after the steroid scandal had ripped through the game in the early part of the last decade, he stood firm in his opposition to drug testing, going so far as to question whether drugs had an effect on performance in baseball ...

Miller retired in 1982, but the pattern had been set. Baseball endured another three industrial actions, including the big one that forced the cancellation of the 1994 World Series. Bleak as that shutdown was, it also represented an endpoint. Baseball has not had a dispute since, while its counterpart US leagues – far more regulated with their salary caps and contract terms – now lurch from lockout to lockout.

“What economic theory tells us with strikes is that you compare the cost of agreeing with the cost of disagreeing,” Dabscheck says. “Both sides found after that strike that the costs of disagreeing were very high. We’re almost 20 years away from that dispute, and there’s quite a lot of water under the bridge ... After that, they said there’s got to be an alternative path. And that path was cooperation.”

The life’s work of Miller showed that resolving the tension between players and leagues is a drawn-out affair, and once the back-and-forth begins, it’s not easily ended. Australia’s major sports have never suffered through significant industrial action, and in the context of union decline across the country (Miller encountered a similar environment), it would be interesting to see how fans react to newly militant athletes. The next generation of sports superstars better get used to long days in conference rooms.

Related Articles

Before Barassi, there was Frank "Checker" Hughes

Will our Olympians bounce back at this year's Games?