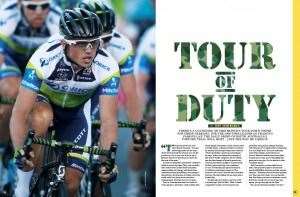

The daily grind of our three-time Tour Down Under champion.

THE WAY I kind’ve look at it,” says Simon Gerrans, “you get three big peaks for the year; three times during the season you can hit peak form. If you use one of those up in January, that’s one less than you have for the rest of the year.”

It must be altogether natural for cyclists to think in terms of peaks. They can consider their entire lives as like those mountain stage profiles writ large, with their lines alternately rising and falling. According to this picture, the practice of riding a bicycle really well is an exercise in resource management. And the resource is pain.

Put it to Gerrans that there’s a touch of video game to all of this – that cyclists, like those digital characters on the screen, have a health meter, a shiny bar that’s run down by enemy hits and special-power exertion. “That’s probably a pretty good analogy,” he says, before invoking the example of last year’s Vuelta a Espana. About 150km into the third stage of Spain’s grand tour, Gerrans had been caught in a mass crash. He felt a pain in his hip, but continued to race. Eventually, the pain forced him to withdraw just before stage 14. The doctors took a look: Gerrans had a hairline fracture. He had ridden for ten days with a broken hip.

“People ask: how did you survive with a broken hip? And I’m like, ‘Well, I wasn’t competitive in the race because I was probably using all my energy dealing with the pain. So I really wasn’t competing at a very high level. If you’re enduring some kind of pain, it just slows you down a little bit. Rather than being able to push your body, you’re handling that pain just to survive. So it’s similar to that computer game.”

Ask Gerrans for a masochist horror story, the kind he’d spin to shock-and-awe the MAMILs during a joyride, and he demurs. “Nothing hurts more than pulling out. The pain of a crash, you can handle that. But when you have to abandon a race, that hurts a heck of a lot more than any agony you go through on the bike.”

He can see the abnormality of it all. “It’s obviously something you’ve got to be able to handle in cycling, the pain and suffering,” he says. “As professional athletes, we’re a bit messed up. We go searching for that pain on a daily basis. Human nature is the opposite. Human nature is to avoid that pain. Obviously there’s something that’s a bit different.”

******

MANSFIELD, the Victorian high-country town known for its proximity to Mt Buller and its place in Ned Kelly lore, is an unlikely place to find a world-class cyclist. Unlikely, but not unreasonable. With its mountain climbs and quiet roads, Simon Gerrans says he can stay peloton-ready when he returns to Mansfield, where he grew up and most of his family still lives.

Gerrans describes his upbringing as pure country: plenty of open spaces and activities for a kid with deep stores of energy. He swam and ran competitively, but the young Gerrans’ first love was motorbikes. His father, Allan, built a motocross track on the property he managed, and as a teenager Gerrans was on a sporting path that was more Chad Reed than maillot jaune.

He laughs at the notion. “Unfortunately, I didn’t quite have the talent on a motorbike that Chad Reed has,” he says. “It was something I was definitely very passionate about. I was a fiercely competitive kid at everything, and I wanted to compete on motorbikes in motocross.”

As it would turn out, one kind of bike riding led to another, if indirectly. While competing at regional-level events as a 15-year-old, Gerrans did what motocross riders do – he crashed, suffering a catastrophic knee injury. He tore three out of the four ligaments in his left knee. “The doctor said it was the most horrific knee injury he’d seen,” Gerrans says. “He patched it up as much as he could for a 15-year-old – he couldn’t completely reconstruct it because I was yet to finish growing …

“I refused to accept I had any kind of issues with it. I went through the rehab, and got it back to as good as possible. I went back nine months or so later, and he said, ‘This is that close to a miracle recovery, I can’t believe I’m looking at the same knee’.”

Gerrans got back on the bike. Twelve months to the day of that first accident, he crashed again, tearing three of the four ligaments in that afflicted left knee – this time he tore the remaining ligament that had escaped unscathed the first time around. “Went back off to the surgeon, he shook his head,” Gerrans says. “He basically said if I hurt this knee one more time, I would need a walking stick to get around. At this stage I’m 16, so that was the eye-opener for me.

“He realised I was competitive, so he suggested a few different sports, namely chess. Then swimming, and finally cycling. He said, ‘At 40 years of age, you might be able to ride a bike, but you’ll be struggling to walk the way you’re going.’ As soon as I could, out of hospital after the knee reconstruction, cycling had taken over my life.”

It was at this moment that serendipity intervened. Mansfield was no cycling hotbed – when Gerrans went to find seven members to form a new cycling club for the town, he discovered a grand total of five, forcing him to join an established club in Benalla which produced the likes of Baden Cooke and David Tanner.

There was, however, a precious and rare resource for the budding cyclist, living just down the road. Phil Anderson had bought a property in Jamieson, one town over from Mansfield, in 1981, while he was in the midst of a pioneering career at the top level of cycling and the Tour de France. The first Australian to wear the yellow jersey would spend his off-seasons in Jamieson, and eventually ended up there after his retirement in the early 1990s. Allan Gerrans leased Anderson’s farm to run cattle, a useful arrangement for the owner because of the long periods during the year that he spent away. Like many people, young Simon wasn’t aware of Anderson’s feats – he was a guy his dad and uncles knew.

“He had motorbikes and mountain bikes, all the fun stuff that you have on a farm. So we used to hang about a bit, but I didn’t quite realise what he did. I knew he disappeared for months on end, but I didn’t know whether he was going away on holidays or whatever. But I knew this guy with big, muscley legs and a good suntan that would turn up every Christmas holiday.”

Anderson recalls that kind of moment as the time he first met Gerrans. “He used to come with his family every Christmas and camp on the river, down below my farm, his uncle’s place. That’s where I first met him; he was camping down the river flat. I think I was in a canoe.”

When Gerrans took to cycling in the aftermath of his second knee injury, Anderson lent him one of his old road bikes, and a few words of advice. If there’s a temptation to see it as the master handing the magic sword and secret scroll to the apprentice, Anderson dismisses the idea quickly. “I had done a level-two coaching course. As part of your training, you have to write a program for a subject. Mine was Simon – it was a pretty basic program, I guess, but it was possibly his first structured program. I can’t really take credit for where he went.

“It’s against many odds that he’s made it to where he is. I’m still amazed at how far he’s gone. He’s always been a gifted all-round sportsman, but he found cycling ... he didn’t show any great talent at an early age.”

Anderson muses about the provenance of Australian cyclists, noting that Cadel Evans emerged out of an even more remote locale in the Northern Territory. “It’s a pretty small community, Jamieson, only 100 residents or something like that. It is strange that such a talent comes from such an isolated, small place. And to be the place – it wasn’t my birth place – where I spent part of my life, it’s very slight odds.”

******

SIMON GERRANS’ start in cycling was relatively late – he was already 19 when he began competing in national-level races. Gerrans believes that Anderson’s patronage was key at this stage. Being “the kid that Phil was looking after” opened some doors, and Gerrans says Anderson’s guidance meant he didn’t lose any time to a bad decision.

One such door led to the Victorian Institute of Sport’s cycling squad, under coach Dave Sanders. Sanders’ initial impression of Gerrans was distinctly underwhelmed. He loves to tell the story that the effects of Gerrans’ injuries – one of his legs is shorter than the other – were not far from qualifying him for the Paralympic team. “When he won his first home race, I turned to the team doctor and said, ‘Can you believe this?’” Sanders says. “It wouldn’t be great for his golf swing, but he makes it work beautifully on a bike.”

Sanders was won over by Gerrans’ moxie, admiring the intangibles he brought to training. He started coaching him outside of the official VIS squad, although Gerrans would eventually make the team. Gerrans was one of those athletes that changes a coach’s way of thinking, Sanders says. “I used to always think that there were three things that make a champion. The first, and most important, was natural, god-given physiology. The other two things were determination and luck. Another Simon – Simon Clarke – is similar. After meeting guys like that, I say the most important is determination. Determination and commitment are at the top of the tree.”

It’s become a grand teaching tool for Sanders. “He’s the role model. I have young guys that, when they complain, I tell them that they have twice the natural talent and more opportunity than Simon ever had.”

After only two full seasons, Gerrans headed off to Europe to join an Italian under-23 team. He was still an amateur, and he recalled having to sell off everything he owned in Australia to fund his last trip to Europe. But he was the top-ranked amateur in France that last unpaid year, and he signed on with French team AG2R in late 2004. The next year, his first as a professional, he had three race wins and competed in his first Tour de France.

“I went through a steep learning curve in my first few years,” Gerrans says. “When I made my first trip to Europe, a lot of Australians now are turning pro at the age – they’ve got four or five years’ professional before the age I turned pro, 24 or 25. But when I turned pro, I knew how to win a race.

“I’ve earned every win or contract. I’ve never been a rider that was paid on potential. All that sort of stuff, I see as a real advantage these days. I was late to start, so I hope I’m late to peak as well.”

The victories that first year had been validation for Gerrans, as was his overall victory in the 2006 Tour Down Under. But even within the cycling world, it’s acutely recognised that there’s fame, and then there’s fame achieved through the Tour de France. Gerrans started riding Le Tour as Cadel Evans’ pursuit of the yellow jersey was elevating the race’s status in Australia – turning it, in Anderson’s words, from the annual televised Francophile postcard into an honest-to-goodness sporting event. In 2008, Evans had come in as the hot favourite, having finished runner-up the year before to Alberto Contador, who was sidelined with his Astana team excluded from the Tour.

Unfortunately for Gerrans, riding for Credit Agricole, his breakout moment would coincide with a tough day for Aussie cycling. True to form, Evans was in yellow by the end of stage nine, and held on to the jersey entering stage 15, a 180km ride in the Alps into Italy, dominated by the presence of the beyond-category Col Agnel. Gerrans found his way into a breakaway up Agnel, which built up a 17-minute deficit at one point as a crash had slowed the peloton. Gerrans held and won the stage, but Evans lost the lead in the general classification to Frank Schleck, and wouldn’t be able to reclaim it from eventual winner Carlos Sastre.

Despite becoming only the eighth Australian to claim a stage in the Tour de France, Gerrans had been overshadowed. “You’ve kind of arrived when you’ve won at the Tour de France,” Gerrans says. “It was probably a bittersweet day for Australian cycling fans. Cadel was going in as the favourite to win the Tour; he lost the lead that day, but I was able to win the stage. All my Grand Tour victories since that day have been very meticulously planned. In that Tour, I had been doing everything I could to get into a breakaway on a stage that suited me. And I just couldn’t get in the right break that was going up the road.

“This stage didn’t really suit me, but I thought, ‘What the heck, I’ve got nothing to lose here.’ I ended up jumping across to a break that had been established before. I was out there with a bunch of guys who were convincingly stronger than me, but I was able to stick with them. It was a win that was unexpected.”

The day after stage 15 was a rest day. In what seems like a cruel joke, the competitors at the Tour de France spend their rest days riding a bike – as Gerrans explains, your body has come to expect the rigour, and responds badly without it.

“Off the back of the win, I was probably pleased with myself. We had a nice, easy ride, enjoyed a coffee, had a couple of glasses of wine the night before. However, my worst day of the Tour de France was stage 16. I’d never suffered so much on the bike as I suffered that day.”

Credit Agricole folded at the end of 2008, which sent Gerrans to the new Cervelo TestTeam (CTT), whose strong roster was built around Sastre and Norwegian sprint star Thor Hushovd. Gerrans enjoyed the best results of his career to date, with top-ten finishes in each of the three Ardennes Classics and a stage victory in the Giro d’Italia. Even with such form, he was mysteriously left out of CTT’s line-up for the 2009 Tour de France. The omission would look even more strange by year’s end, when Gerrans won a stage in the Vuelta, making him the only Australian to claim stages in every Grand Tour. Dealing with the vagaries of team politics in Europe is something bike pros learn to live with. “As a foreigner trying to break into a European team, you have to be outstandingly better than the European,” Gerrans says. “Because they’ll always take preference for one of their own over someone from the other side of the world.”

******

GERRANS joined Team Sky for the next two seasons, adding the 2011 Tour of Denmark to his palmares. When the long-held ambition to form an Australian team came to fruition for 2012, Gerrans and his proven record in the one-day classics and grand tour stages made for an obvious target.

Gerrans described joining Orica-GreenEdge as a homecoming, linking up with people in team management he’d known since the start of his career. The Gerry Ryan-backed project made a very deliberate point of putting an Australian stamp on the team, something not lost on its lead riders. “Having what we call the Aussie DNA of the team, it’s created a fantastic culture,” Gerrans says. “The leaders in Orica-GreenEdge, we lead by example. That’s one differentiation we have with other teams.

“If I’m under no pressure from team management to win or it’s not an objective of mine, I’m back to getting bidons, I’m riding the front for my team-mates, I’m doing things that I expect team-mates to be doing for me in the races I’m trying to win. It’s a real credit to the guys who put this team together for creating this culture.”

Orica-GreenEdge enjoyed near-immediate success, particularly for such a new team, and Gerrans was at the centre of it. He won the National Road Race Championship, then claimed his second Tour Down Under in January in the tightest possible finish with Spanish star Alejandro Valverde. A few months later, he claimed the statement win of OGE’s debut year, taking Milan-San Remo in a sprint finish over Fabian Cancellara and Vincenzo Nibali.

Taking down one of the monuments of European cycling was hugely significant, and was the high point of a successful first year for the team. But the Tour de France thing – the different level of fame – would affect the tenor of the season. Orica-GreenEdge failed to win a stage, and sprinter Matt Goss’ campaign for the points classification came up short. “I always say that the Tour de France results are the biggest, because that’s what everyone around the world knows,” Gerrans says. “Within cycling, I’m as proud or more so of winning Milan-San Remo, because it’s a monument within the sport. But ask anyone on the street what Milan-San Remo is, it’s two towns, if that.

“In our debut season, we achieved so much across the entire season – we won races from January through to September. But we didn’t win anything at the Tour de France. It was that little thing missing from our first season, so to get back on our second season, it was the monkey off the back.”

The 2013 Tour started with the kind of folly that risked being the main impression OGE left that year. The team bus became stuck at the finish line, causing carnage during the stage. The organisers went back and forth on moving the finish, and it turned into Chinese whispers in the peloton, with some riders getting mixed messages about where the finish was. The confusion led to a mass crash with six kilometres to go.

Orica-GreenEdge’s bus driver came in for plenty of notoriety, but the team was sympathetic. “It’s like if you were trying to parallel-park into a tight space in front of a restaurant,” Gerrans says. “Try to do that in front of 200 million people.”

Ahead of the Tour, Gerrans and the team had locked in on stage three, the last of the opening set of rides around Corsica. Tracking around some ruggedly handsome coastline, picturesque even by the standards of the Tour, Gerrans’ team-mate, Simon Clarke, led out in a bold display. The bunch was together with three kilometres to go, and Daryl Impey was trying to set up Gerrans for the sprint, matched against the 2012 winner of the green jersey, Peter Sagan. The two crossed the line with their heads down – neither celebrated, because neither was sure who had won.

“The last thing I wanted to do was celebrate a stage win, only to find out I hadn’t won it afterwards. Couldn’t think of anything worse,” Gerrans says. “We looked up and were basically side by side. I think Peter knew he hadn’t won it, I got the impression, but I didn’t know. It was only when I was told a couple of minutes later.”

Orica-GreenEdge was still having to answer questions about the bus incident, but more good news would quickly follow as the Tour moved back to mainland France for stage four, the team time trial in Nice. If the stage three victory had been the product of careful planning, the time trial came as a surprise. With 17 teams heading off before them, OGE was third at the checkpoint, but raced over the back half to beat the leading mark by a single second.

Orica-GreenEdge had its signature moment, emblazoned across front pages at home and everywhere else. The victory put Gerrans in yellow, the sixth Australian to wear the famed leader’s jersey, sharing a list that started with Phil Anderson. A day later, true to the team-first philosophy, Gerrans passed the jersey on to Impey. “You can see there’s great camaraderie on the team,” Anderson says. “There’s great pride and patriotic feeling, even though a good portion of the team is foreigners ... You can see that in what Simon did in passing on the yellow jersey.”

******

ORICA-GREENEDGE’S achievements have only helped an already flushed feeling for Australian cycling. “The big change I’m noticing is how many more cyclists there are out on the road and getting involved in the sport. If us getting results over in Europe is encouraging people to take up the sport in Australia, it’s all for the better.

“That’s great for the development of the sport, but what it’s also done, for all these people who are new to cycling, it’s given them a team to support. It feels like we’re the home team of Australia.”

Gerrans appreciates that his career has landed in the midst of a boom period. He lives in Monaco during the European season, although he’s quick to note that his wife Rahna and their two children spend much more time there than he does. Rahna was a junior cycling champ, which would raise hopes for the kids – Dave Sanders said he already has his talent-ID eye trained there. For now, Gerrans hopes they benefit from growing up multi-lingual, rather than learning French in the peloton.

“We’re very much involved in the community, my kids go to school there. But yeah, as soon as you say you live in Monaco, people say, ‘Ooh, that must be tough.’ There are some downsides – we all live in apartments – but it’s a great place to live, aside from the glitz and glam. It’s one of the places where you can spend as much money as you want, but there is a community that lives there 12 months a year.”

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open