How to train like a world record-breaking rider.

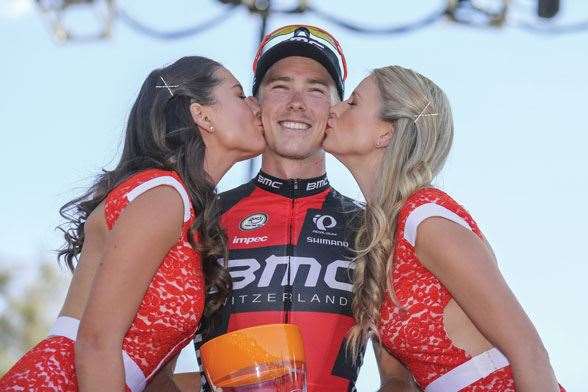

Rohan Dennis has been an up and coming Australian cyclist reeking of greater potential for some years now, while somehow staying below the radar of popular fame. Which will happen when you’re one part of a team pursuit and team time trial outfit, even if you’re winning world championships (2011) and Olympic silver medals (2012). But the 24-year-old from Adelaide is bloody famous now! A win in the Tour Down Under will do that. And when you then back it up a few weeks later with a successful assault on the world One Hour record, you put your name in lights. The Hour record is cycling at its most pure – and most cruel. How far can you get around a velodrome in 60 minutes? If you’re Rohan Dennis, you can ride 52 kilometres and 491 metres. He broke the record by about 600 metres. It’s a record numerous cycling greats have attempted – and most have failed. Dennis pulled the pin on his track career in 2012, heading into the professional road racing ranks after the London Olympics. That path led to him being picked up by BMC Racing Team in mid-2014, riding alongside countryman Cadel Evans. Heard of him? It’s been a stellar run since then. His team won the gold medal in the team time trial at last year’s Worlds. Then, as he explains, he didn’t even mean to win the TDU. But he definitely meant to break that Hour record, and he told Inside Sport editor Graem Sims how he did it.

BEGINNINGS

“I used to swim. I did medley and breaststroke and a bit of backstroke. I’d been swimming since I was four, and started racing and did squad from seven through to 15. But then a talent identification program came through our high school, at Endeavour College. They did it out at the South Australia Sports Institute; they tested kids at a heap of schools around the state. I only just scraped in with my shuttle run; I was actually bettered by some of the girls in the group that got picked. Initially, I thought I’d use the bike as sort of cross-training for my swimming, but after four months I went to Nationals and on the road I was the fastest first-year in the under-17s. I thought, ‘Next year, I’ll be a second-year under-17, which is the top age, and already I’m actually technically the best in Australia for my age ... I’m actually good at this!’ I’d never ridden a bike at all seriously before. I’d always thought bike riders were weird for wearing Lycra. But the funny thing was, I was wearing Speedos every day! That was probably the dumbest thing I’ve ever said. I still swam five times a week for a while, but after four months on the bike I gave the swimming away. Obviously the results came quite quickly, and that makes it easier. But it was more of a social sort of sport. You didn’t get to see girls in bikinis every day, but you did get to see a lot more than just a black line. It was more interesting. Not as mind-numbing.”

STEPPING UP

“When I first started cycling, my VO2 was, I think, 73 or 75. Which isn’t bad, but I really noticed it going up around the age of 17. We did a lot of testing with a new way of training for the individual pursuit at junior worlds, and by then it was 91.6, which is just lower than Brett Aitken and Stuart O’Grady, who got 93.6 and 92.8 in Adelaide. I’d done one test and I think I was 83 or 84 VO2, and then over a three-month period we did a lot of one-legged efforts on the ergo. The theory was that if you only use one leg, you can overload it, so your body will work harder for that one leg rather than try to work two legs, if that makes any sense. So you can actually do 60 percent of your four-minute power on one leg, but you can’t do 120 percent of your four-minute power on two legs – it’s like bumping your power by 20 percent. So you overload it for two to three minutes at a time and you swap from one leg to the next, constantly, and you do that twice a week. And over three months I think I went from 84 to 91 VO2 and my power went up from 477 to 519 over four minutes as well.”

THE HOUR

“It was just a thought that came to me that I wanted to have a crack. It happened just out of the blue last September at Road Worlds in Ponferrada in Spain. When I found out Jens [Voigt] was doing it and people were talking about it, I sort of shot my mouth off and said I’d smash him. I didn’t think a whole lot about it – I just said it. And the team was, ‘Okay, let’s do it then.’ They knew I was a time trial specialist and obviously had the experience with technique on the track, knowing when to go hard and when to sort’ve float so that you recover somewhat during the effort. But they wanted me to do it straight after road worlds, whereas I was a little bit tentative when it came to doing it so quickly. I’d set my mind on finishing my season straight after the road worlds. I thought we should do it after Tour Down Under when I know I’m going to be going close to 100 percent anyway, and I’ll be mentally fresher as well.”

TOUR DU

“My win in the Tour Down Under this year was a bonus – something I wasn’t even planning on trying to do. I was actually 100 percent there for Cadel, and it just ended up being that I got that little gap and took the win. Basically the Hour record was the whole purpose of doing Tour Down Under, so I got some adaptation and some race legs as well. I needed the extra intensity [of the race] to take into the hour record, to take me to another level above training. And that was all I was sort of thinking about the whole time. I was trying to keep my cadence up so I didn’t get bogged down in a big gear, so I could get used to what I’d have to do on the track; you have to be able to spin on the track or you won’t be going anywhere. Obviously riding the track is a little bit similar to what you do in the swimming pool, which is something I could bring into it – not think about anything, just look forward.”

GETTING TECHNICAL

“A lot of your riding skill comes down to confidence. When you’re confident in your equipment especially, your tyres and your bike, it helps a huge, huge amount. In the past, when I was in the under-23s, I had a lot of bad luck in general with crashes, and I started to not be so good in the bunch or even around a flat corner. I’d start to be a little bit tentative. But when things start to go your way, and when you know you’re going to win a race or you’re in for a good chance to win, your skills seem to get better – it’s a weird thing. You can take those risks without having in the back of your mind, ‘What if I’m going to crash?’ You just sort of do it because you have to do it. It’s a funny thing: sometimes I feel like I’m probably one of the worst cornerers in the whole peloton, and other times I think there’s no way they’re going to drop me. It’s probably something I missed out on a little bit – not being in big bunches and riding in Europe when I was younger. But with the amount of riding and training we do up and down hills, you tend to find your limit and you work on your own strengths in races.”

THIS IS LIVING

“The team expects you to take everything seriously, so you don’t just go out and drink and eat everything you want. It has to be a pretty good result to celebrate – it can’t just be, ‘Oh, we just came third!’ Or, ‘Hey, we finished a race! Let’s have a drink!’ It’s fairly strict, but at the same time they do have a lot of fun. They don’t expect you to live on top of a hill and not talk to anyone, just counting your calories and all that sort of stuff – that’s bordering on being psychotic if you do that too long. I live with my girlfriend here in Girona – she rides as well: Melissa Hoskins. She just won the gold medal on the track at Worlds in France with the Australian women team pursuiters. So we’re both sort of in and out a lot lately, not seeing a whole lot of each other. Eating wise, we just try to keep it as healthy as possible, so when we go to the supermarket we try to stay away from the chocolate and lolly aisle. Obviously sometimes I can’t help myself. But when I do break out I make sure I do it properly: I think that’s the key. When you’re going to eat the crap, you don’t drag it out over a couple of weeks, you just get it all out in one hit. So if you’re really anal about your food for a long time, and then you decide you want a block of chocolate and you go and buy a 300g block, you just finish it. And then I won’t touch it for a long time after that again. So instead of dragging it out and having a bit every day, you just have one big whack and then stop it for another month or longer.”

CADEL

“Cadel has helped me a lot – even though I’ve really only spent six months with him, since the Vuelta last year. We then did the road worlds, Tour Down Under, plus nationals. They’re the only four races I did with him, but in the Vuelta he helped me a lot; after stage 14 I was having a bit of a rough time, mentally more than physically, but feeling a little bit fried. And we had a long transfer that day and he spoke to me after the race, and he made everything a lot clearer – he mentored me through the last week of the Vuelta, and my performance went up in that last week. I have to take my hat off to him – he handled that situation very well and got the best out of me during my first grand tour finish. Then in the Tour Down Under he was the leader, and it wouldn’t have been easy, being technically his last race as a pro, and someone else coming up and taking his win that he’d worked so hard for. But he was really supportive of that, and it showed a true champion who can actually not just get shitty that someone else has taken his leadership role, when it came to the results anyway. He just helped me through and made sure that he put me in the best possible position to win the race. I just wish I was in this team a little bit earlier.”

– Graem Sims

Related Articles

Track cyclist Rohan Dennis' hour of power

How Australia's beach volleyball women train