Why the superstar Serb still isn't the crowd favourite.

Novak Djokovic – slayer of the two-headed tennis monster “Fedal” – is coming off his third year as No.1 in the last four seasons. He’s an exemplary champion, sometime comedian, husband, father and sporting statesman. So where is the love?

WHEN WE last featured Novak Djokovic in the pages of our magazine back in January 2008, he was “The Djoker” – the cocky young upstart and impersonator who took the mickey out of fellow players en route to his first major final at the 2007 US Open. He lost that final in straight sets to Roger Federer, then mocked his missed chances, saying he had a title for his tennis memoir: “Seven Set Points”.

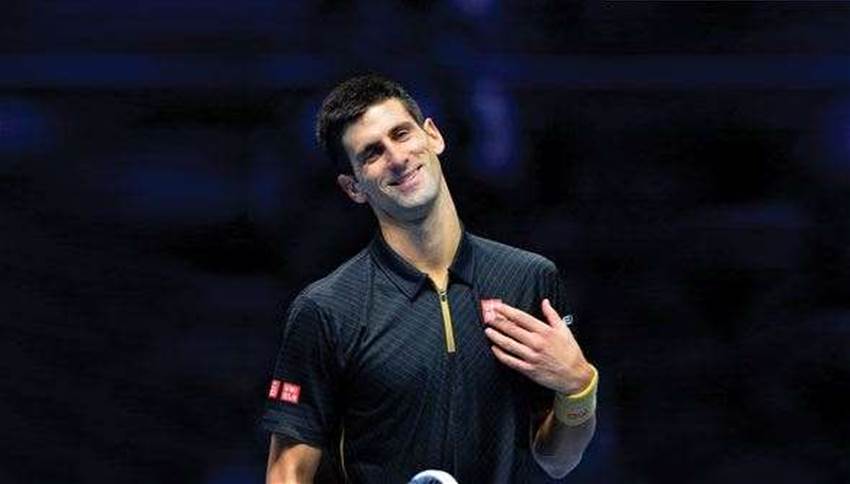

Seven years on and The Djoker is the king. Has been for three of the past four years. “I’m at the pinnacle in my career,” he crowed after winning the ATP Finals in London, hammering the elite field with gob-smacking scorelines (US Open winner Marin Cilic 6-1, 6-1, Australian Open champ Stan Wawrinka 6-3, 6-0, Tomas Berdych 6-2, 6-2). “When he’s playing well,” said Kei Nishikori, the only player to take a set from Djokovic, “I don’t think anybody can stop him.”

The 27-year-old Serb long ago secured his place in tennis lore, as slayer of the two-headed tennis monster that is Federer and Rafael Nadal, aka “Fedal”. Hard to miss the last-man-standing symbolism of the No.1 alone and unchallenged at season’s end – Federer withdrew from the London final with an injured back and Nadal shut down his season to undergo an appendectomy.

Djokovic, meanwhile, finished the year full of running. The proud new dad even proved fatherhood wasn’t the career kibosh it’s often feared to be, going undefeated since the arrival of son Stefan in late October. At Melbourne Park this month, a fifth Australian Open win would make Djokovic the most successful men’s champion in the Open era.

Yet there’s a nagging sense that the people want their Djoker back; that Djokovic, the impressive No.1, hasn’t matched the popular highs of his trash-talking Djoker days, when he was a staple of YouTube and late-night TV chat shows. Respect for an admirable champion yes, but where is the love?

In London, Djokovic lost his only set against Nishikori in their semi-final, when he became visibly upset at the crowd clapping his missed first serves and cheering when he double-faulted to drop serve. His thin-skinned reaction to “some provocations that I usually don’t react on, but I did” – illustrated how much Djokovic likes to be liked. Though often kitted out in villainous black – and he wears it well – Djokovic doesn’t relish being the guy in the black

hat. Hearing the crowd cheer your mistakes is a problem never faced by Federer and Nadal, who don‘t have fans ... so much as mass worshippers.

Even though he has supplanted them at the top, Djokovic does not command the rusted-on devotion of the Federer and Nadal armies. According to one commenter, Fedal followers comprise 90 percent of the “tennis fan establishment”. While their heroes rule the game, their fans dominate even more the chatter on web sites and social media. Both have close to 15 million Facebook followers; Djokovic has five million.

Underappreciated, much? Djokovic is the leading major winner (six titles) and match-winner of the past four years. His three seasons as No.1 (2011/12/14) equal Nadal, whose injury woes prevent him from being a durable No.1. The 42-chapter Djokovic-Nadal rivalry is the longest-ever in men’s tennis; at 23-19 to the Spaniard, it’s far closer than Nadal’s at-times painful mastering of the Swiss master. Yet Federer-Nadal is still held up as the showpiece tennis rivalry. Perceptions are lagging behind reality.

It isn’t as if Djokovic is a boring automaton on the court. His all-court game is as crisp as his shirts, with long strokes, a cracking down-the-line backhand and a lean, sharp silhouette as streamlined as a shark’s. Thanks to his freakish bendy ankles, Djokovic has introduced an eye-popping flexibility to the men’s game. Like Kim Clijsters, he can slide out wide in splits formation and not just return the ball, but rifle it back for a winner from extreme defence. “You never know when the guy’s behind in a point,” Andre Agassi noted, “because it seems like he can hurt you from every part of the court.”

And Djokovic is unfailingly a gracious loser. “He knows how to play now on the big stage,” he said of Wawrinka, who ended his 14-Slam run as a semi-finalist or better at last year’s Australian Open, 9-7 in the fifth. “You could feel that with his game. He’s really taking it to the opponent and stepping in. When you’re playing like this, the only thing I can say is congratulations.”

As a media performer, Djokovic rivals Federer. Both are articulate and multilingual – Djokovic in English, Serbian and German – but the Serb works harder at courting the media than either Federer or Nadal. “Many of you stayed this late,” he said, touched at the turnout for his 4am victory press conference at the 2012 Australian Open. “Thank you.”

“We have to,” grumbled a bleary-eyed reporter. “I know you have to,” replied Novak, “but make it look like you want to.”

After his 2013 Australian Open win, Djokovic apologised for an abbreviated post-mortem as he had a plane to catch. He had a peace offering – a box of fine, hand-made chocolates, which he passed around himself, clambering up the stairs of the theatrette. The media literally eating out of his hands. Federer, for all his loved -up pressers, never shared around the Lindt balls.

NOVAK DJOKOVIC took the hard road to glory. A more comfortable life beckoned, coasting on his talent at No.3, behind once-in-a-lifetime champions Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal. He could have banked his millions in Monte Carlo, owned castles in Serbia, partied in Belgrade and attended a stadium or two named after him. But he wouldn’t accept playing second banana, even to the two greatest Grand Slam winners in the game. Nor was Djokovic content with being the first player to defeat Nadal and Federer in the same event – Montreal in 2007 – as a 20-year-old. Weeks later, he was in his first major final at the US Open. Six months later, he was Australian Open champion, ending the Fedal duopoly with a win over Jo-Wilfried Tsonga – the first major final in three years to feature neither Federer nor Nadal.

Djokovic was going after the impossible: reconfiguring the Federer-Nadal two-hander into a triumvirate. He still had a long way to go after that 2008 Australian Open breakthrough. “After that,” Djokovic recalled in London, “I lost most of my matches against [Federer and Nadal] in the major events. I went through my doubts. But those two guys, and the matches I played against them [he’s 19-23 against Nadal, 17-19 against Federer] made me a stronger player. Made me realise what I needed to do to improve, to be in the position one day to be No.1 and win Grand Slams. So I do feel that those rivalries contributed to my success a lot.”

Djokovic isn’t in the greatest-ever conversation. Nadal has twice denied him a career Grand Slam at Roland Garros. But he’s making serious inroads. Owner of seven major titles, he’s sure to overtake Andre Agassi, Ivan Lendl, Jimmy Connors and Ken Rosewall on eight. A final tally of 11 would be realistic and would place him in the rarified company of Rod Laver and Bjorn Borg – the tennis deities BF (before Federer). Even if his tally falls short of Federer’s record-17 majors, or Nadal’s 14, nobody could accuse Djokovic of winning in a soft or transitional era. His title wins (and Andy Murray’s for that matter) carry extra degree-of-difficulty points for coming in the most top-heavy age in the game’s history.

While he battles for hearts and minds, Djokovic has won a world of respect for big on-performances. His tour-de-force 2011 is equal to the best seasons of Nadal and Federer (except, of course, Federer has had multiple seasons as a triple major winner). Djokovic conquered the indomitable Nadal for seven-straight finals in this stretch – including at Wimbledon for the No.1 ranking. Last in the sequence was Djokovic’s shirt-ripping victory in their gruelling 2012 Australian Open final, which ran for a record five hours and 53 minutes. Down 4-2 in the fifth, Djokovic won five of the last six games to nail the most gladiatorial, if not the greatest, major final ever.

Against Federer, Djokovic is 6-6 in Grand Slams; his victory over the Swiss in a vintage Wimbledon final last July was not just the high point of his year and “the best-quality Grand Slam final that I’ve been part of”, but a turning point in the tide of public opinion. Djokovic played with visible fear in the final. He’d gone 18 months without a major since that Melbourne Park marathon, dropping two finals apiece to Nadal and Murray. He’d recruited Boris Becker to help him mentally in big matches. And he had a proud seven-time champion come roaring back from match point down in the fourth set, and breathing fire. But just when the great Federer had all the momentum, with the world and his wife – not to mention Wills and Kate – behind him, Djokovic braved a breakpoint and took the fifth set 6-4 in one of the all-time-great Wimbledon deciders. Even Federer tragics had to concede the Djokovic A-game beat the master at his best, or close enough to it. If Federer had won with lights-out tennis, well and good. But even his worshippers didn’t want their man to win by Djokovic faltering. The best man won.

REALLY, what did the younger Novak Djokovic do that was so objectionable? He stopped the impersonation skits years ago, not because they offended (although Nadal took exception to the wedgie-plucking routine), but because the comedy was intruding on the main act. “I was serving at 4-4, 30-all in an important match,” Djokovic recalled in a TV interview, “and a guy in the crowd goes, ‘Hey Novak, do Sharapova; make us laugh!”’

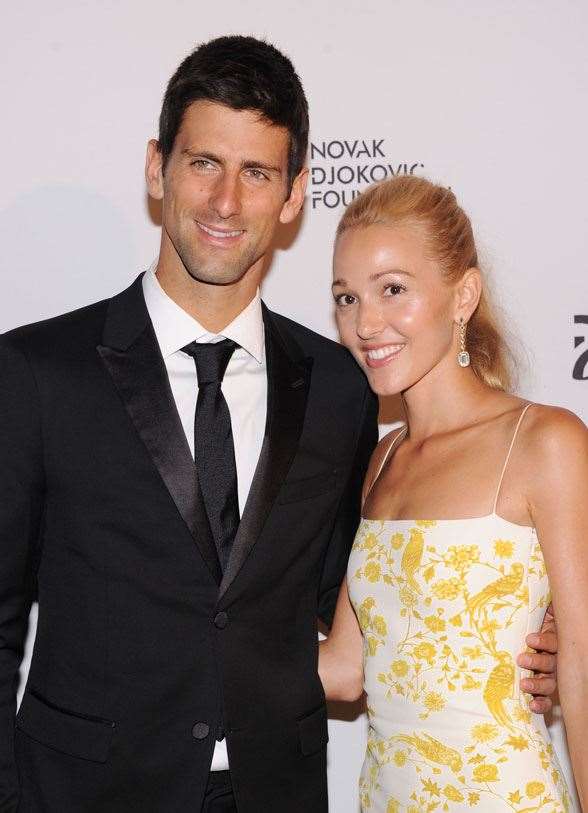

Some players were irked by the Djokovic family – his abrasive father Srdjan, mother Dijana and younger brothers (both aspiring players) Marko and Djordje, at times all outfitted in T-shirts bearing his likeness or nickname, hanging over the court and getting in the face of Novak’s opponents. At Monte Carlo in 2008, even the serene Swiss maestro hollered at them, “Be quiet!” But the Djokovic clan has been an infrequent tour visitor since Novak told it to stay home and – not coincidentally – went on to his best season. Moral support since has been largely provided by Djokovic’s high school sweetheart, Jelena Ristic, now his wife.

Patriot and peacemaker is a tough gig – one that Federer and Nadal don’t have to deal with. As the world’s most famous Serb, Djokovic has done more than anyone (along with his tennis-playing brethren) to rehabilitate the image of his once-outlaw nation, without ever serving up virulent nationalism. “I am happy when I have my own group of fans supporting me in a fair way, not provoking my opponent,” he said at the 2009 Australian Open after defeating Bosnian-American Amer Delic, while flag-waving, football-style fans went all Fight Club on the grounds. Serbia couldn’t ask for a better ambassador. Ironically, the Serbian icon, as Chris Bowers reveals in his just-released biography The Sporting Statesman: Novak Djokovic And The Rise Of Serbia, is half-Croatian on his mother‘s side.

What hurt Djokovic most in terms of peer and public relations was his gamesmanship with injury; his tendency to call the trainer at opportune times. Federer called him out in a Davis Cup clash back in 2006: “I don’t trust his injuries; he’s a joke when it comes to his injuries.” Retirements in big matches – notably at the 2009 Australian Open as defending champion – only increased suspicion. Djokovic was derided for being one match short of a career Grand Slam in pull-outs ... The low point came at the 2008 US Open when a caustic Andy Roddick mocked Djokovic’s supposed injuries in an on-court interview. “Bird flu? Anthrax? Sars?” Roddick quipped, listing his opponent’s ailments. “He’s got about 16 injuries right now.” Djokovic won their quarter-final in four sets, and departed to Bronx cheers.

But that inglorious incarnation was officially buried in Melbourne on the stifling night of the 2012 Australian Open final, when Djokovic out-duelled Nadal in a spectacle as brutal as two stags fighting over a harem. Nobody who witnessed that warrior moment would ever again question Djokovic’s stamina or stomach for a fight. “You’re going through so much suffering; your toes are bleeding,” he said afterward. “Everything is just outrageous, but you’re still enjoying that pain.” The quitter had turned tennis iron man.

Djokovic's win over Roger Federer in the 2014 Wimbledon decider was the turning point in the tide of public opinion. (Photo by Getty Images)

Djokovic's win over Roger Federer in the 2014 Wimbledon decider was the turning point in the tide of public opinion. (Photo by Getty Images)ROGER Federer never saw himself as a world-beater, though his obsession with the game was obvious as a kid. Rafa Nadal was French Open winner at 19 but many doubted his clay court success would ever translate to faster surfaces – including Rafa himself. But Novak Djokovic was always certain of his destiny: world No.1 and Grand Slam winner. Other players have goals and dreams; Djokovic had a mission.

His professionalism even as a kid is a standout memory to many. Childhood coach Jelena Gencic told biographer Chris Bowers that at their very first hit, in the mountain resort of Kopaonik where his family owned a pizzeria, Djokovic arrived with his bag expertly packed, right down to the banana, just like the pros he'd watched on TV. He was five. As a young teenager, he told his expat Aussie coach Ladislav Kis to instruct him only in English, as that was the tongue of the pro tour. Nikki Pilic, who worked with Djokovic from ages 12 to 16 at his tennis academy outside Munich, recalls that he was always early for practice, having stretched and warmed-up beforehand, untold.

Ernests Gulbis, the Latvian maverick who broke into the top ten in 2014, was one of the juniors at Pilic’s academy. At the French Open last June, Gulbis lost to Djokovic in his first Grand Slam semi-final; Djokovic was playing his 23rd. “He was really professional already at that time,” Gulbis recalled of the teenaged Djokovic. “I remember we had a friend, a Croatian guy who was all about the girls at that age already. He was dressing up. He was looking good, putting on perfume, sunglasses, going to talk to the girls. I see Novak, he’s going to stretch. And Novak told me that, yeah, you can have anybody. Can have all the girls in the world, you know. But to be really successful in tennis, you need to work. That’s a kid who is 15 years old.”

For all his drive and discipline, Djokovic faced physical rebellion from his own body. He’s twice had surgery for a deviated septum that continues to cause breathing problems on court. At 18, a coach believed he was seeing the ball a fraction late and told him to get his eyes checked. He’s played with contact lenses ever since. Foot injuries led to the creation of three sets of orthotics – for grass, clay and hard courts. Finally, food allergies were uncovered as the cause of his sapped energy in matches. Djokovic was diagnosed with a gluten intolerance in mid-2010 – a remarkable discovery for a kid who grew up on pizza and pancakes at the family restaurants (he also doesn’t get on with tomatoes). Already as lean as a greyhound, Djokovic trimmed down on his new diet. At 188cm, he is an inch taller than Federer and Nadal (both the same dimensions at 183cm and 85kg), but a sleek five kilos lighter. When he turns sideways, Djokovic all-but disappears, except for his pelt-like head of hair.

The health issues put into perspective some of Djokovic’s past physical struggles. Few tennis champions have overcome more obstacles – and that’s leaving aside his bombed, blighted country. Up until the early 2000s, Serbia was a pariah state, synonymous with ethnic cleansing and war crimes. In the midst of Yugoslavia’s bloody self-destruction, a seven-year-old Djokovic appeared on a children’s TV show and declared he would be No.1. Even then, he realised given the turmoil in his country, “It seemed like I had a one-percent chance to do that.”

Djokovic returned with an American TV crew to the concrete basement of his grandfather’s apartment building in Belgrade, where the family sheltered during the 1999 NATO bombing campaign. He is remarkably sanguine about those times. But then, a victim complex is not useful for a budding tennis champion.

Australians will see the champion in his prime at Melbourne Park, Djokovic’s most successful Grand Slam. Another major, another chance to distinguish himself from the legendary Federer and Nadal. Djokovic is the only man to three-peat at Melbourne Park (2011-13) and a win this month would see him overtake Federer and Agassi as the most successful men’s winner of the Open era. He’s the favourite on paper, if not with the crowd. But even winning over the gallery, you suspect, is not beyond this relentless self-improver, not after the on-court miracles he’s already wrought. Djokovic may be destined to be forever bracketed with Nadal and Federer, but like their epic on-court clashes, he won’t always be coming off second.

- Suzi Petkovski

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

The Aussies at The Open

.png&h=115&w=225&c=1&s=1)