Earning a place in the hearts of Melburnians hasn't been easy for the Storm.

Billy Slater (left, 250 NRL games) and Cameron Smith (club record 263 games) march off AAMI Park after beating Penrith in a thriller this year. (Photo: Getty Images)

Billy Slater (left, 250 NRL games) and Cameron Smith (club record 263 games) march off AAMI Park after beating Penrith in a thriller this year. (Photo: Getty Images)THIS AFL-MAD MATE of mine was a timeworn emblem for Melbourne’s attitude to rugby league. Let’s call him Ted Kowalewski. Back in the 1980s, when witless stubby-holders were lobbing their bumper-sticker broadsides over the Murray from both sides, Sydneysiders still derisively referred to Aussie rules as “aerial ping-pong” and Melburnians fired “cross-country wrestling” back over the border.

My life having been a tale of both cities, I’d always followed Sydney’s Dragons and Melbourne’s Magpies. Despite my urging him to try and understand the “bum sniffers” game – he enjoyed that particular insult – Ted disliked it as a matter of principle. But like all Melburnians, Ted loved a great sporting contest (being a Richmond fan, he had to find his kicks somewhere), and he and I, together with a Kiwi rugby union snob, would gather round the box at Origin time. Back then, we all went for NSW. The Victorians I knew (perhaps influenced by me) understood then that Queensland was to New South Wales what South Australia was to Victoria – bad losers and in-ya-face winners, with little-brother chips on their shoulders the size of boulders.

It began to shift in 1995, when the second-ever Origin game held at the MCG, and that year’s series, was sealed by Queensland with a scrambling last-minute try. From then on, Ted began to regard me with a kind of haughty suspicion. I was made to feel like some kind of dirty propagandist who’d concealed the truth all this time. Ted would test my reaction as he emitted the odd heretical cheer for the Cane Toads. It was annoying. The rah-rah nitpicker followed suit.

By the time Melbourne Storm came along, who were winning games with scrambling last-minute tries which produced the best-possible result for the city – a scrambling, last-minute premiership – Ted was half-hooked, but cynical, not only about the Storm’s 1999 title, but also its tenure in Australia’s “sporting capital”. Ted reckoned it was like invading China: it happened every so often, but China was too big to notice and too busy to care. If Melbourne’s broader population was to augment its football interest with any other code, it was more likely to be union, which had rushed into the void created when Super League rent, then rented-out, the great northern game.

Those two Origin matches just before the Super League schism had provided the ARL with record crowds. Melburnians enjoy a sporting event with symbolic clout. The League had been seriously contemplating a legitimate Melbourne club, and had done its homework. Then Murdoch’s mob came the grouter.

Now that league was re-unified, Ted was wary of being used. Melbourne Storm was funded by News Ltd, and cobbled together from the wastes of defunct Super League teams. Ted didn’t want some bloody franchise; if anyone was going to impose the northern game on Melbourne, he wanted a club of his own.

The Storm’s founding heroes retired, to be replaced with a trinity of Queenslanders who kept winning games for them, and Queensland. Slater, Smith and Cronk were looking almost like bona-fide Melbourne heroes, even when they played for the detestable Toads, who were by this time getting full-throated support from my mates. I took to watching Origin on my own, unless I happened to be in Sydney.

Ted’s now a paid-up member, loves the Storm with a passion, and has even taken a liking to the game itself. When they were stripped of the 2007 and 2009 titles for salary-cap breaches, Ted’s attitude typified that of most Storm fans: “No one else won those premierships, and Storm would have won them even if they didn’t have Inglis under the cap.”

Ted now fits his AFL-watching schedule around the Storm’s home games. I myself struggle when they play Saints. After all, the mighty Dragons have been tainted anyway with that “Illawarra” thing, and at least Storm represents one town. That’s how I rationalise my own conflict.

******

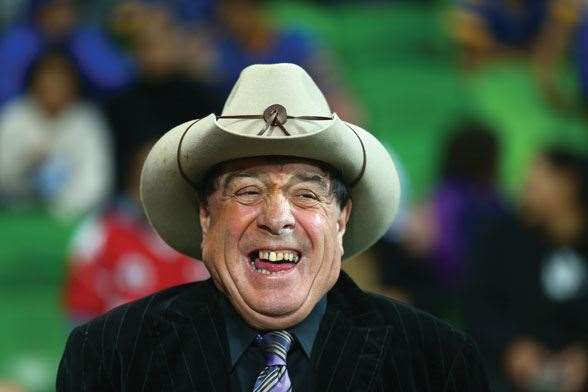

AS LORD MAYOR OF MELBOURNE, John “he’s my bro” So made a good Hong Kong businessman. Which made him a good Lord Mayor, oddly. He was never in danger of being typical. John seemed to desire a lot less power than the office affords, but we suspected he had, in fact, a lot more. He certainly had fun. What would the annals of Town Hall be without him? A little more intelligible, maybe, but let’s not quibble.

The chuckling chairman, number-one ticket holder for most things branded “Melbourne”, including the Demons and Victory, was overjoyed the day in 2007 he got up in front of the Storm faithful, proclaimed Melbourne the greatest city in the whole world, and introduced a new Melbourne sport that sounded like a medical condition you might keep hidden from your family.

At the time Melbourne was so euphoric, it was even gratefully receiving the semi-hostile satellite of Geelong as its own. At least the AFL premiership, which had resided among foreigners, was back in Victoria for the first time since 2000. The day after that historic Cats victory, the Storm had beaten Manly in the NRL grand final. In front of a rapturous crowd at Olympic Park, where the Storm paraded the Cup, The Mayor couldn’t contain himself. “On Saturday, Geelong win the AF ow, and now” he proclaimed with gleeful disbelief, “we gotta wubby lee! Hwa hwa HWAAAAA!” This was Bobby Hawke, naughties style. Our bro stopped short of declaring an impromptu holiday, but the big weekend had nevertheless become a long weekend, judging from the size of the Monday crowd. Happily, rugby league, along with Chinese Lord Mayors, no longer seemed so minor in Melbourne.

Of course, Melbourne had got itself a wubby lee in 1999, when the Storm won that first premiership only two years into its existence. But right from the start, the sword rugby league used to penetrate Melbourne – one initially wielded by former Australian winger, ex-Broncos CEO and quondam Super League boss John Ribot – was double-edged. Many initially were chary like my mate Ted, but there was plenty to like about the new club. Despite its Murdoch funding, the Storm was neither a Super League nor an ARL club. It was brand new. Ribot, determined to make it work, quit his desk at Super League to set it up. He was a visionary, and whatever he did to stitch that little purple patch on the teeming tapestry of Melbourne’s sporting culture, it worked.

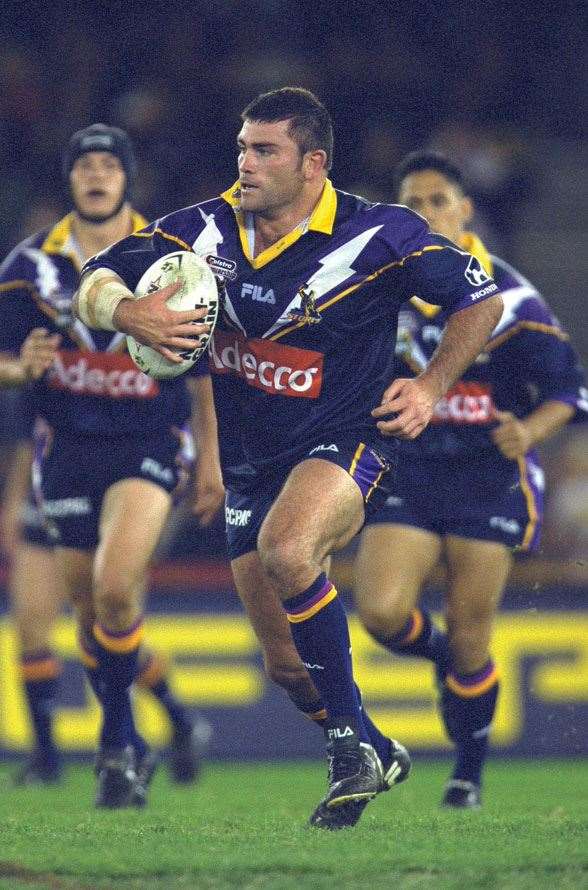

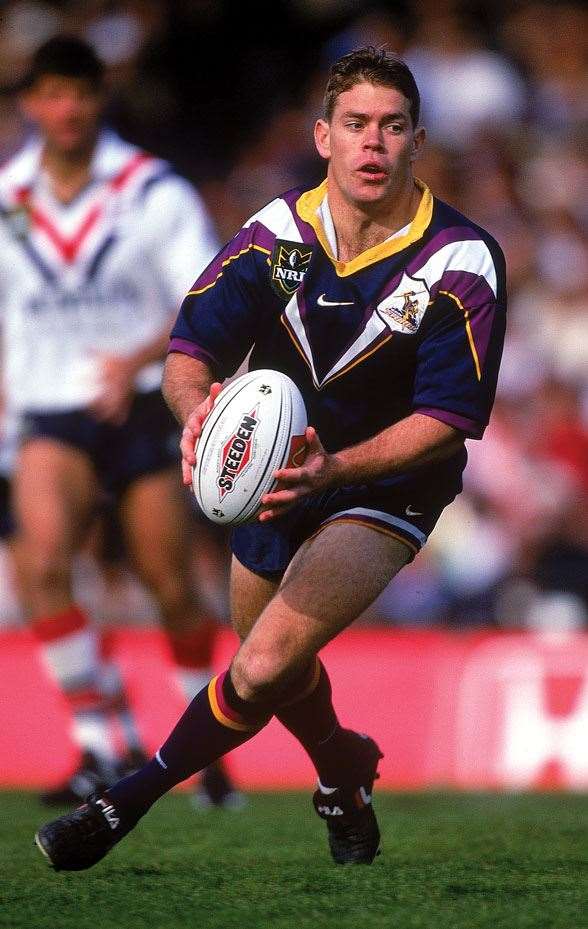

Greg Brentnall, the former Canterbury and Australian back who famously almost played Australian rules for South Melbourne (now Sydney Swans), was at the Storm from the beginning. He’s now its development manager. Brentnall believes much of the Storm’s success, and its supernatural ability to overcome, has been about careful recruitment, with leadership the goal. The early group, consisting of strong characters like Glenn Lazarus, Robbie Kearns, Tawera Nikau and Brett Kimmorley, enforced the “no dickheads” policy. “Craig and others are still strong on that. Right from the start they were strong personalities. Then Stephen Kearney came and they set the standards for the Smiths and Cronks who lead the place now.”

Brentnall, inaugural coach Chris Anderson and long-time Canterbury chief Peter Moore, who helped manage the list, all brought with them a cultural gene from the great Canterbury sides of the 1980s. The Bulldogs were renowned as a family club, mentally tough, famous for nurturing greatness in men who might not, at first, have been considered great anywhere else, like the Mortimers. “We were all relocated and had family. This made us a pretty socialised group off the field. We didn’t have that extended network of support. We created our own and that’s continued until now, 17 years later.”

Football manager Frank Ponissi agrees: “Ribot started a strong club, very family oriented. We did feel isolated away from Sydney. We’ve also had good, strong coaches. But in the last two years, losing those great players put pressure on the leaders to display those qualities of mental strength even more. Billy Slater was being criticised in the media and people have been saying he’d lost the number-one position to Inglis. His play was superb against Inglis in that game.”

That game, against Souths in May, was another routine piece of timely magic. Slater, playing, apparently, for his Maroons “1” jersey after a brief season of untypical errors, bamboozled them with a two-try cameo. This was the Storm after all! How could they lose a game in which, for the first time in RL history, four players were reaching the combined 1000 game mark together – Slater, Cronk, Smith and Hoffman – and Bellamy was coaching his 300th game (for 202 wins!)? They pulled off, of course, a win against talk of being over the hill. The Big Three starred. This mob sends its supporters a powerful message: “Believe in us. We’ll do the rest.” Fans don’t just take to football codes for their own sake, unless it’s in the culture of their family. Fans often become fans when they engage with heroes, and then their clubs. They learn all about the sport after that.

Heroes are a big reason why Victoria is more openly “Queensland” than it was once. “It’s pretty hard to get away from the influence of the Big Three,” says Brentnall, “and during that time Queensland have dominated. Initially, support might have been for NSW because it was their games that they brought down here.”

But before they had heroes, Melbourne Storm – with News Ltd help – worked its hardest and smartest. They quickly nestled into the Melbourne culture. Brent Silva, general manager of NRL affiliate, the VRL, admired the Storm’s approach from the start. “The Storm engaged the local community and local sport. They’ve never been afraid to work with AFL and soccer clubs with things like their coaching exchange programs, where they get ideas from each other.”

From the world of the “working man’s sport”, where public behaviour often made the AFL seem prudish by comparison, the Storm were exemplary citizens. At Olympic Park, their old ground, they interacted with the locals like no other team, applauding their audiences, making their gratitude known.

But what really won Melbourne over has been a good old dose of a kind of inverted shock doctrine, one happy, magical, euphoric event after another working on the mass Melburnian mind, until it seemed betrayal to support anyone else. The Storm specialises in giving its fans dramas with happy endings.

The Storm has a compelling simplicity, at least in its home town; an innocence of belief. Imagine being a Trekkie, or a Hulkamaniac, without having to suspend disbelief in order to accept the implausible events unfolding before your eyes. In their first season they won their first four games, and Melbourne, a little amused, began to take notice of this curious sideshow of rugby league cowboys. Brentnall knew from the start what would get them in. “Melbourne was always going to embrace the sport if they could get a high-quality team in the competition.”

The Storm made the finals in 1999, was murdered by St George-Illawarra in its quarter final, applauded for its guts in making it as far as they did, and no one thought any less of them. But Melbourne squeaked in against Canterbury the next week, then Parramatta. Led by Lazarus, they’d rolled away the stone twice, and now found themselves up there with Saints on rugby league’s holiest of days.

They were making up the numbers, surely! Not on your life. This time, they rejected the script and put in the first of many an extemporaneous masterpiece after being down 14-0 at half-time, with a little help from an opposing five-eighth named Mundine, and centre Jamie Ainscough. They ran on. They hung on. 20-18. The premiership was, incredibly, theirs.

Ever since, game after game, Victorians have thrilled to the Storm screaming into action with seconds on the clock and stealing victory, or winning the unwinnable, prodigies of will and skill. We’ve watched significant rivalries grow with at least five other clubs. We watched them negotiate an entire purgatorial season for no points, right to the end, with grace and dedication. Sydney felt an obligation to dislike them, but Melbourne finds them more admirable as time goes on. After the salary cap breaches of 2010, that respect only increased.

“A lot of people in Melbourne were disappointed,” says Silva, “but they were more sitting back waiting to see how the Storm would respond. The coach and players got on with it and won a premiership a couple of years later. The administration built the brand to become one of the most respected in Australia.”

******

WHEN THEY BEGAN, the politics were Byzantine. There was that Sydney-Melbourne thing. The Victorian Rugby League was a little cautious back then. There was the mutual enmity of the (then) ARL and John Ribot, instigator of Super League, Queensland legend, whose determination to break the NSW hegemony actuated his Melbourne initiative.

Then there was media. Super League had been a Murdoch baby. Ribot had worked for them. Channel Nine, the official free-to-air carrier, was owned by Kerry Packer. A passing knowledge of Australia’s media would tell you what that meant.

Ribot’s perspicacity and determination were infectious. Melbourne even negotiated a deal to have its matches televised in China. But there’s no substitute for winning, and the Storm hit the ground winning. Channel Nine finally turned up in round 17 of their first season for a live telecast. But the Storm have since been deprived of live coverage at home. “We were able to get free-to-air and have an impact in 1998-99 because we were successful,” says Brentnall. “But then in 2000 Channel Nine got the AFL rights and up until 2013 we had no free-to-air. Getting the next generation of kids interested without any coverage was a big drawback for us.”

Opportunities for the NRL to grow the game in Australia’s second-biggest state off the back of the Storm’s success have been abundant. Most have gone begging. Sydney forever carped about the help Melbourne received from News Ltd, but the Storm was given little from the newly formed NRL. When enlightened people in Victorian government saw that this was not just about a Melbourne club, but about expanding the game’s supporter base and generating revenue, things began to change. “It was mid-2005 that we really got our first leg-up from the game,” according to Brentnall “We got three games of Origin promised to us over the next seven years, which was the catalyst for a number of things. When we got these marquee games, the Victorian government said, ‘Well, we want you to be part of the place,’ and built the $300m stadium we’re now playing out of. They also gave us grassroots funding that enabled us to put on six extra staff. We were able to start creating awareness and turn the next generation into rugby league supporters. We didn’t have TV coverage, but staff being able to go out into the schools was a big part of building support for the Storm and the game.

“Since 2006 we’ve had a 350 percent increase in participation. It’s still not a huge number, but it’s given us the opportunity to run our own high-performance programs. It took us 13 years to get a home-grown NRL player, but we’ll see a lot more behind that. Mahe Fonua was our first, we’ve had Young Tonumaipea come through and we’re starting to see the benefit of the money we’ve spent in trying to create a pathway,” Brentnall reports.

“Around that time [’06-07] the VRL began working more closely with the Storm,” says Silva. “Victorian Rugby League player registrations went from 875 in 2006 to 2860 last year. The open high school comp has been incorporated into the national GIO Cup.”

A lot of recruiting magic still has to happen for Melbourne to sustain its success, but it hopes to have a lot more choices in the next few years as a result of a strong junior base, according to Brentnall. “The under-20s [which feeds into the national championship] was the first step in that pathway and then the club agreed to fund the under-18s. Last year we were able to field an under-16s team as well, which has given us a progressive pathway. But our membership is reflecting our work. We reached 15,000 last year and we should go well past that this year.”

They do what they can for the local clubs, attending carnivals and community events, signing jumpers and meeting locals. Three players for other nations in the World Cup last year came through the Victorian competition.

Silva believes the NRL is beginning to understand Melbourne’s benefits. “In the past it’s been pretty Sydney-centric, but now with this ‘whole game’ approach, they consider everybody, from the five-year-old through to the Australian captain, from people who help in the canteen through to administrators. They want to say they are truly a national organisation, so the Victorian market is very important, as is the West Australian market, and having a footprint in Adelaide and the NT. Melbourne obviously provides tremendous commercial opportunities, being the second-most populous city in Australia. You don’t need a large percentage of it to be quite significant for the NRL. The Storm’s 15,000 members is probably 50 percent more than three or four years ago. The NRL grand final last year was a record for a televised rugby league event in Melbourne. The ratings for Origin were significant as well.”

******

MELBOURNE'S MORE INTRACTABLE AFL fans can still be derisive. The Storm’s attendance average has climbed to 17,000 – poor by AFL standards, but it’s a false comparison. The historical attitude to crowds has always been vastly different between the codes. This, too, is in the throes of change. The rise of sports radio station SEN has helped. When AFL luminaries like Kevin Bartlett conduct weekly interviews with “the man with the coolest name in sport”, Cooper Cronk, and Storm get fantastic coverage, you can hear Melbourne’s consciousness changing.

Melbourne’s Pacific Islander population is also participating in record numbers. Greg Brentnall, a phlegmatic Wagga Wagga boy who talks like Terry Daniher, continues to do his bit in the northern states. “In 2012 [the last of the three games promised to Melbourne] Ricky Stuart trained the team at AAMI Park here, and at that stage was very anti the game being here. They’d lost six series in a row and this was going to be the series decider. He was all about taking two games to Sydney and not giving a game up to Melbourne. I told him all about the stadium and what had been done for grass-roots footy. He was surprised. It made me realise how that message isn’t out there that the game is bigger than just NSW and Queensland.”

This year, Brentnall went to Queensland for an occasion that included the announcement of the Origin team. As a member of the original NSW Origin side, he felt justified being there, the only Cockroach in sight. “I tried to get across that we’ve now got a $500 million stadium as a result of Origin coming here and six extra staff to try and grow the game. That was a bit of incentive for going: to try and spread that message a little bit. People don’t realise what effect the concept has had and what effect it’s had on the growth of the game.”

******

THE DAY I BEGAN WRITING THIS, AFL icon and the game’s greatest evangelist, Tom Hafey, died. Hafey, a broad-minded man, came to love rugby league during his time with the Sydney Swans, and read everything he could. Tom was probably the best barometer of the acceptance of rugby league in AFL’s home. He adored the Storm, spoke at its functions and regularly visited. He was forever publicly holding them up as paragons of professionalism and sportsmanship.

I suspect it was Tom who piqued Kevin Bartlett’s interest. “KB” was one of “Hafey’s Heroes” in the 1960s and ’70s, when Tom coached Richmond to four premierships. They remained the closest of friends. “Tom saw a bit of himself in Craig Bellamy,” Bartlett said the day after Tom’s passing.

“The Saturday before Tommy’s death,” says Frank Ponissi, “we had Tom’s grandsons at the Manly game, and they met the coach and players.” Not far away, another of Tom’s grandsons, Jackson, was at Tommy’s bedside. Tom was drifting in and out of consciousness, but Jackson had the iPad going and they watched the Manly game to the end – a scrambling, last-minute win for the Storm. It was the last sporting event Tom saw. He died on the Monday.

Bellamy and Ponissi were among the last to see him. “Last time he talked to our players, a year ago, he had them eating out of his hand,” says Ponissi. “They went out pumped and ready to play – and it was only training.”

Tom’s death was widely reported in Sydney. The previous day, we’d lost Reg Gasnier, the greatest Dragon of all. It was big news in Melbourne.

Ted called me the day Gasnier died, to commiserate, I guess, with a Saints fan. I’d known the Magic Dragon had been ill for some time, but I didn’t expect Ted to know that much. It was enough that he understood Gasnier’s significance. Next day, I called to inform him of Tommy’s passing. Ted said, sadly, “Last week, Bellamy wrote a column in the paper. The week of his 300th game as coach, and the story’s all about his friendship with Tom. That says a lot.”

It’s all Storm can do, to keep winning in the ways they have.

Related Articles

Feature Story: Moving the Needle

LIV Golf alters format for season-ending championship