9 / 20

You can find two versions on YouTube of Cathy Freeman’s run in the 400 metre final at the 2000 Sydney Olympics. One is accompanied by Bruce McAvaney’s (and Jane Fleming’s) marvellous commentary – you probably don’t need reminding, but why not? Bruce: “Cathy lifting ... Takes the lead ... Looks a winner ... This is a famous victory. A magnificent performance. What a legend. What a champion ... ” Jane: “What a relief.”

There’s another, sans commentary. Just crowd noise. Sorry, Bruce, but it is arguably even more compelling. Anyone there that night can never forget the decibel level in that stadium as she swallowed the leaders inside the last 100 metres. A roar redoubled ... then redoubled again. An arena – an entire nation – united in orgasmic delight (and yes, relief) as our poster girl for the entire Games actually delivered on the “promise” she had first shown in her breakout year of 1994, winning a gold medal for Australia on the track, the sacred heart of Olympic competition.

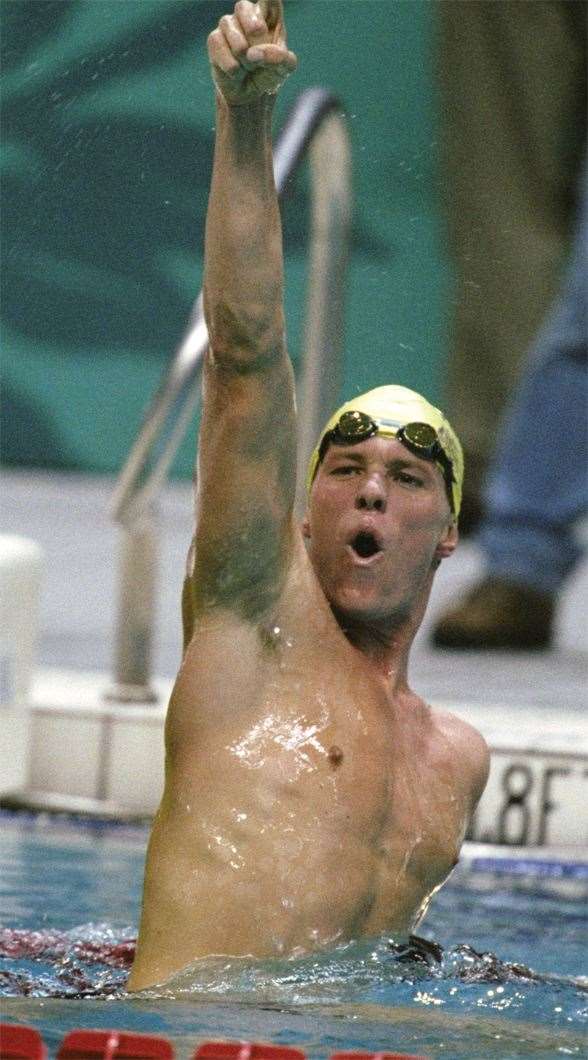

Australia has enjoyed a truly remarkable rise in Olympic competitiveness this last 20 years: just 14 medals (3 gold) in Seoul in 1988; then 27 (7 gold) in Barcelona; 41 (nine gold) in Atlanta; 58 (16 gold) in Sydney; 49 (17 gold) in Athens; then 46 (14 gold) in Beijing ... that’s 63 gold medals won in the life of Inside Sport. Why choose Cathy’s win, in what has been suggested by some to have been one of the weaker 400m fields assembled at that level, won in a time that wouldn’t have got her on the podium four years earlier? How could it exceed the smashing guitars of the 4x100m men in the pool, Perkins’ golden double (and almost triple) in the 1500m, Hackett’s repeat in the same event (gold, gold, silver), et al?

It wins because those arguments about Freeman’s times don’t wash. Of the top 400m times in history, sure, Freeman’s time in Sydney comes in well down the pecking order (49.11, equal 48th), whereas her silver in Atlanta comes in 14th, with Marie-Jose Perec’s gold in that race the sixth fastest time ever run. The reason Freeman’s win does rate by any measure is due to the muddying of waters and times in the bad old days of the 1980s, before the systematic dope cheating of the Eastern bloc nations was curtailed. World’s fastest 400m? East German Marita Koch in 1985. Second fastest? Jarmila Kratochvilova in 1983. Etcetera. Then Perec’s time in Atlanta. Then a Soviet runner in ’85. Then a Czech in ’83. Then Cathy Freeman in Atlanta. Sure, she was a tad slower in Sydney, but she was running from lane six. In the cool of night, not the dry heat of Atlanta. There can be no doubting Cathy’s class, even up against the most tainted times in history.

Sure, there has been pressure in the pool, and in the field, and everywhere else. But there has never been more pressure on any single Australian athlete in history (let alone the last 20 years) than in our feature event at our home Olympic Games. Resoundingly won. And resoundingly celebrated by all. No doubt about it: for Australians, this was the best Olympic moment ever.

– Graem Sims