This famous clan proved that Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu was the "ultimate" way to bring down an opponent ... whatever their size.

IN MIXED MARTIAL ARTS (MMA), especially its most popular manifestation, Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC), it’s axiomatic that a good grappler will mostly beat a good striker. This is relatively new wisdom.

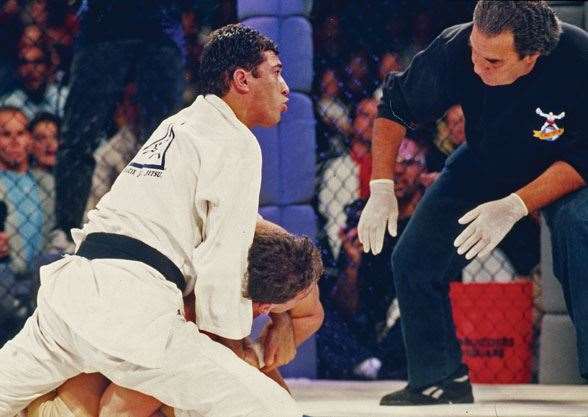

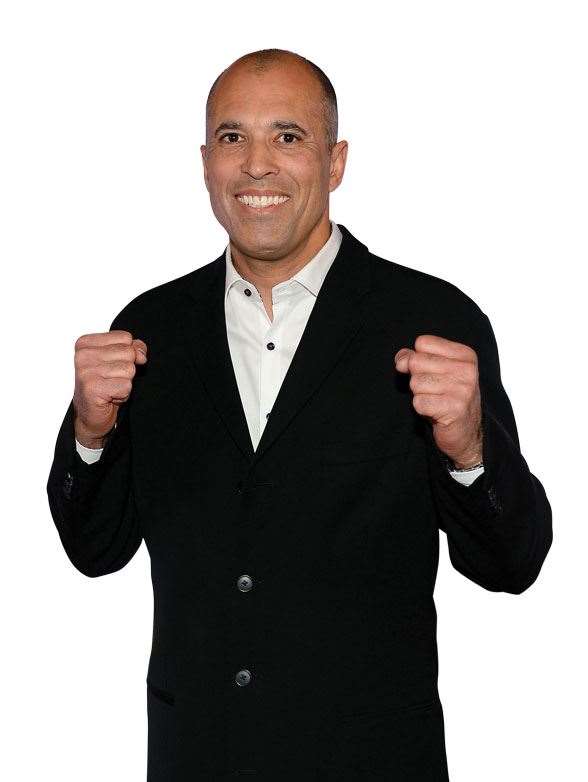

The grappling arts entered the MMA world via the efforts of Royce Gracie in the 1990s when he won three of the first four Ultimate Fighting Championships. Often fighting much larger exponents proficient in shootfighting, boxing and many Asian martial arts, Gracie dramatically proved the efficacy of ground fighting using Brazilian jiu-jitsu.

BJJ, or “Jitz” as it’s come to be popularly known, is a way of nullifying the advantages of big, powerful opponents. Despite the power required to take a man down and apply submission holds, BJJ is all about bodily mechanics rather than outright strength. In a purely BJJ competition, as distinct from the more widely-known MMA, two expert exponents will engage in a grappling contest that amounts to a form of martial chess, one joint-lock, choke or other manoeuvre after another being applied or intensified each time an opponent moves – much like a boa constrictor tightening its grip each time its victim takes a breath – until the “checkmate” is applied. This comes in the form of an opponent’s unconsciousness, a dislocated joint, or extreme pain resulting in voluntary submission.

So how did that amazing melting pot, Brazil, wind up being the home of something that sounds like a Japanese martial art, and why is that martial art synonymous with one family? It began when Mitsuyo Maeda, one of Japan’s top groundwork experts, was sent overseas by judo’s founder, Kano Jigoro, to demonstrate his art to the world. Maeda’s theory was that combat almost always occurred in distinct phases: striking, grappling, the ground phase and others. The challenge for a fighter was to ensure the fight remained in the phase that best suited his strengths. This concept of the fight as a process is central to BJJ.

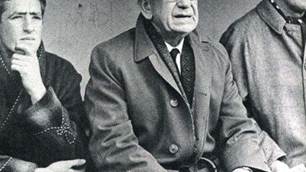

Maeda left Japan in 1904 and visited a number of countries, giving “jiu-do” demonstrations and accepting challenges from wrestlers, boxers, savate fighters and other martial artists. Maeda fought hundreds of victorious challenge matches. He arrived in Brazil in 1914, where he met part-owner of the American Circus, Gastao Gracie. Shows featured the formidable Japanese judoka. Maeda became known in Brazil as Conde Koma – the “Count of Combat”.

In 1917, 15-year-old Carlos Gracie, Gastao’s eldest son, watched a demonstration by Maeda and decided to learn judo. Maeda accepted Carlos as a student. Carlos, a small man who weighed around 60kg, learned the art, then tested and refined it in hundreds of matches, which he opened to practitioners of all styles and skill levels who answered his advertisements. Eventually, he passed his knowledge on to his brothers.

Carlos, his brothers Oswaldo, Gastao, Jorge, and Helio, Luis Franca and Oswaldo Fadda, built on their extensive knowledge of judo, using it as a basis for a new way of fighting and eventually popularising the new martial art of Brazilian jiu-jitsu. Brazilian legend has it that Carlos was never defeated. Other members of the Gracie family took up the art, and many traditions the Gracies began have continued.

The tradition of “open challenge” is still an important aspect of the Gracie legacy. The Gracie Challenge, inaugurated by Carlos, was the precursor to today’s MMA and UFC. Before that, the idea of different martial arts challenging each other in organised tournaments, or formal bouts, was non-existent.

Carlos also introduced an innovative nutritional regime, the Gracie Diet. He was an intelligent student, and his diet was based on Hippocrates’ maxim “let your food be your remedy”. His diet ensured practitioners were operating at optimal level, illness-free, by the time a competition came around. This diet was aimed at controlling the body’s pH levels with foods that naturally combined nutrients to that end. It precluded the consumption of alcohol and any pork and pork products.

The Gracie lineage of BJJ exponents is long and wide. It began when Carlos taught his sons Carlson and Carley, who taught their brothers, sons, nephews, and cousins. The idea of televised Ultimate Fighting was invented by Rorion Gracie, who was trying to introduce Brazilian jiu-jitsu to America. One of his students, movie producer John Milius, helped him come up with the idea of the “octagon” – a space visible to spectators from which fighters cannot escape by using the ropes.

Rorion proposed that Royce should be the first member of his clan to compete in UFC – which was then an open-weight tournament – rather than the enormous and powerful Rickson Gracie. Royce was small, skinny, and, for a Gracie, inexperienced. He would fulfil Rorion’s vision of proving the superiority of Brazilian jiu-jitsu to the world. The concept of UFC has moved away from Rorion’s vision, but the Gracie legacy is enormous, now that martial arts have become popular entertainment.

Related Articles

Before Barassi, there was Frank "Checker" Hughes

Will our Olympians bounce back at this year's Games?