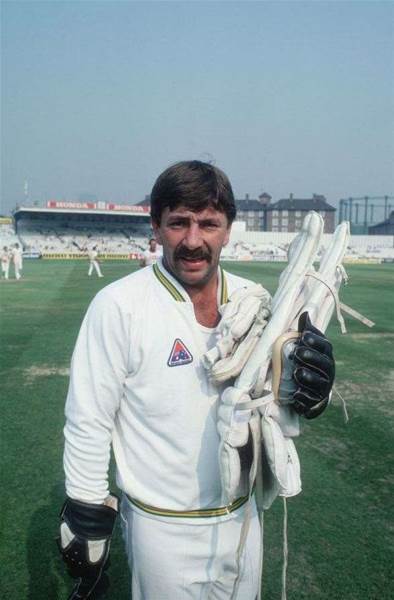

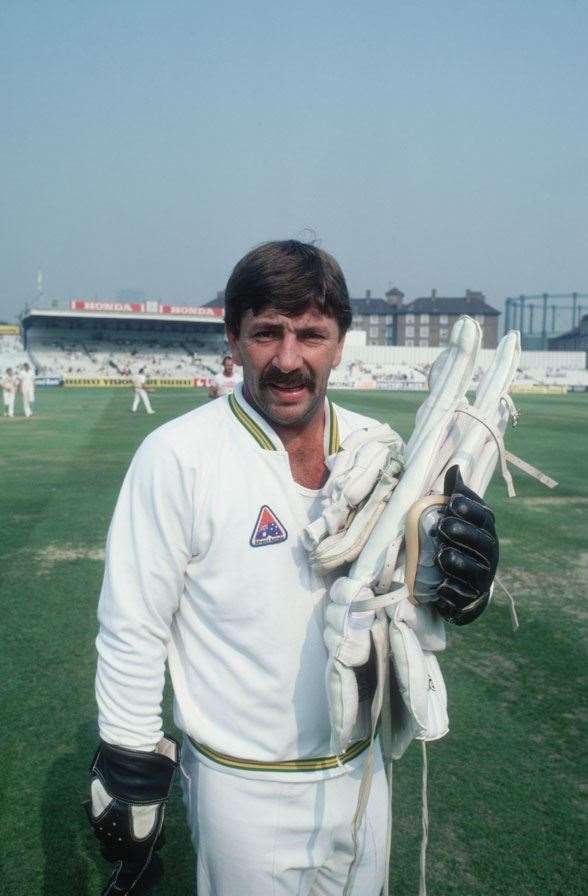

In his playing days, he was much more than our favourite larrikin.

You wouldn’t think it, but Rod Marsh was responsible for a lot more than maintaining Australia’s larrikin edge. In fact, he changed the way a wicketkeeper caught, padded-up and batted ... forever.

It’s hard to pinpoint why Australia’s ex-wicketkeeper, Rodney Marsh, has been an “innovator”, but he has. He was a burst of newness from the start. From the time of his controversial inclusion in the Australian team through to today, Marsh has been the sort of man to make good things happen; often unprecedented things. Part of it has been his unabashed love for the game. Part of it has been his deep understanding of it.

Marsh’s tenure as Australia’s wicketkeeper was a turning point in Australian cricket for many reasons, and after he retired, he went about effecting more turning points. What he did differently then and now was to ... bring Rod Marsh to the role.

In his various positions in the sport over the years, Marsh always did one thing well: he understood how to remove barriers to winning cricket; his judgement, unlike other ex-players’, was unhindered by self-regard and ego. Straight-forward yet complex, conservative on one hand, revolutionary on the other; brusque, yet compassionate, Marsh was, and still is, often misunderstood.

From the beginning of his first-class career, when he scored 102 against the touring West Indies in 1968-69, but was a long way from being Australia’s best wicketkeeper, Marsh held deep respect for cricket’s traditions, and yet had decided the game he loved should go about things differently. Indeed, he knew he himself needed to. In a few short years after his disastrous Test debut in 1970-71, he turned better-performed rivals for the national job into admirers, leaving little doubt as to his merit.

It took time for Marsh to marshal all the powerful components of his bulk to the extent that he became a world-class ‘keeper, but once he did, he left little question. He always brashly and matter-of-factly stated his worthiness for the job long before he had it, genuinely believing he was born to it. And if he was wrong, he said, he was going to make it as a batsman instead – an ambition unheard-of from Australia’s previous custodians.

“Bacchus” had a bad habit, since boyhood, of trying to catch every snick, no matter where it was headed, even third slip! Experience taught him when to leave it, but the habit of covering vast territory quickly never left him, and his lateral movement was unprecedented. Many ‘keepers before and since took “diving catches”, but Marsh did something else, propelling himself at great speed, horizontal to the ground, glove extended. The catches and takes a lot of ‘keepers dive to take – those which make the highlight reels – are grabs which Marsh, swift and sure of hand and foot, would’ve taken on his feet. When he dove, it was because he had to, and when he did, he wound up in uncharted territory for a ‘keeper, before or since.

Marsh was the first Australian wicketkeeper picked for his batting first, and the outcry was great. It didn’t take long for him to prove the wise ones correct. He grassed some critical grabs against England in 1970-71, earning that famous moniker “Iron Gloves”. His batting, already proving indispensable at number-seven, barely made up for the hurtful misses. However, there was something unique about a ‘keeper who took it to the opposition. His batting, by turns explosive and careful, was simply beginning to make the rebuilding Australians look better, stronger.

Even before his standard suddenly improved, he was a presence – visible, confident, expressive, mobile, joyous, admonishing, haranguing, laughing, glaring. Everyone – team-mates, opposition and spectators – felt that presence. By the time Ian Chappell took over in the Fifth Test, Marsh was already a valued advisor. As time went on, he was conspicuous for his tireless efforts to keep things upbeat. He’d be racing to the other end with Greg Chappell at the end of an over, practising golf shots, or talking and laughing with anyone in slips who’d listen between balls, perching over the stumps, arms outspread to provide a target for fieldsmen.

Marsh focussed on fitness more than any other ‘keeper ever after that series, training alone and with his mate Dennis Lillee, and turned up next season as trim as Rod Marsh could be.

Like Ian Chappell, Marsh wasn’t fond of drawn games. He believed miracles were always possible, and privately thought so at Adelaide in that first series when Bill Lawry refused to go for a win. Marsh strove for victory at every opportunity, and couldn’t understand why an Australian captain would not think the same way.

As time went on, Marsh’s natural exuberance and willingness to experiment in order to gain every small advantage was there for all to see. He even got out to a reverse sweep – in 1972-73! – off Intikhab Alam after scoring 118 against Pakistan. That century was a true innovation: he became the first Australian ‘keeper to score a Test hundred, after belting 236 against the tourists in a State match.

All through his playing career Marsh was never satisfied with the suitability of ‘keeping gear. He even put steak in his gloves once when ‘keeping to the ferocious pace of Lillee and Thomson. But despite his desire to protect his hands, he really preferred to feel the ball, and said he’d rather have ‘kept bare-handed. By the end of his career, he’d approached the manufacturer numerous times to trim the rubber on the palm of the gloves and make them tighter-fitting.

Every little calibration was designed to increase his mobility and his naked experience of the ball. Marsh went for lighter boots, spoke to manufacturers about taking much of the weight and bulk out of pads, and eventually, in a spontaneous act toward the end of his career, snipped the flaps off the top of his pads, which had always annoyed him. In fact, he’d never been convinced that pads were necessary at all for a ‘keeper.

Possibly the greatest demonstration of Marsh’s uniqueness was probably also his greatest act of sportsmanship: in the Centenary Test of 1977, which Australia went on to win by

45 runs. Derek Randall threatened to pinch it for the Poms on the final day. He was 161, the English 140 out from victory, when he edged Greg Chappell. Marsh, diving forward, took it on the half-volley and Randall was given out. The only man in the world who’d have known Marsh didn’t catch it cleanly was Marsh himself, and he conspicuously said so. We were all disappointed, but our esteem for Marshy had increased immeasurably. Randall was recalled, was soon out on 174, and Australia scraped home by 45 runs. He’d scored a match-saving 110 not out already, and if Lillee was the Man-of-the Match, Marshy was its character; its soul.

Whether people know it or not, he’s been that way in his various crucial roles ever since, and cricket in general, particularly Australian cricket, should be ever-grateful for him.

Related Articles

The Wrath of Khan, 1976-77

Ponting details how to get Aussies on top